Study Your Bible in English

That is, study it in English if English is your native language, and when your knowledge of biblical languages isn’t up to the task. Face it. For most people, even those who have some study of biblical languages. Different levels of study of the languages provide different levels of benefits. But for most people, the best idea is to study the Bible more carefully and thoroughly in the language they actually know.

There’s a sense among people in the pews that knowledge of Greek or Hebrew provides some sort of magic key. This even affects pastors, who want to look up a particular Greek or Hebrew word in order to spice up their sermons or to find the real meaning of a text. The problem is that looking up a particular Greek or Hebrew word and then wielding that definition like an axe, chopping chips out of the text, more often misleads than enlightens.

For laypeople, the approach is often to find “the meaning of the Greek” through a commentary, or even worse through a concordance such as Strong’s. A correspondent once sent me a complete translation of a verse derived from glosses (single word or short phrase translations of a term) in Strong’s, in which not one single word was translated correctly in the context. One could, however, track the English words back through the concordance to a Greek word which did, in fact, occur in the verse.

Words do not have singular meanings. It is more accurate to say they have fields of meaning, sometimes called semantic ranges. I look out the window in front of me and I see a number of things that I would call “trees,” yet they are not identical. Some are larger, some are smaller. At some point there is the transition between “bush” and “tree,” and “bush,” again, covers a range of items. The actual boundary is set by usage. Now that I live in Florida, I have to realize that Floridians call things “hills” that northwesterners would call mounds or bumps, while there’s nothing in easy range of here that a northwesterner would call a mountain.

If you have the time and inclination to learn the biblical languages, by all means do so. But if you don’t, what can you do?

Here are some suggestions:

- Don’t just go to the most literal translation you can find. People often believe that by using the New American Standard Bible, the English Standard Version, the New Revised Standard Version, or something similar, they are getting closer to the source language. In one way, these versions do get you closer to the original, an I don’t have a problem with using any of them. Just don’t assume that they take care of getting you closer to the original.

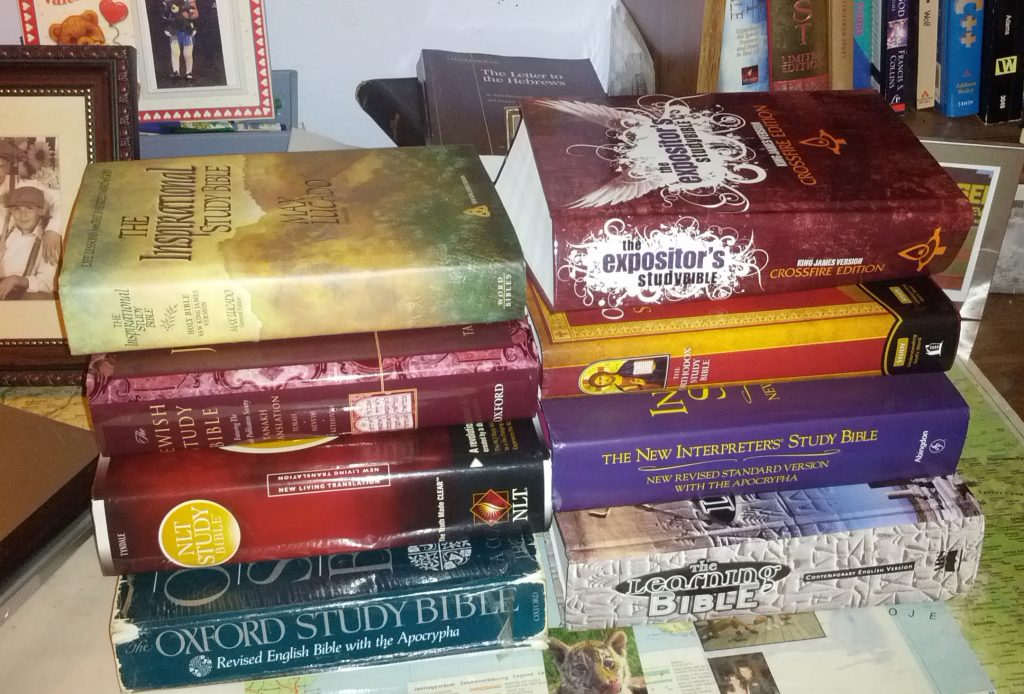

- Instead of #1, choose 3 or more translations. Try to find translations that are committee translations and represent different theological backgrounds. For example, the NASB, NIV, and NLT are all done by evangelical translation committees. They represent three different approaches to translation, but their committees are all conservative. The NASB is formal, the NIV is a kind of compromise version, while the NLT is dynamic or functional. (There are many more differences in approach to translation. Check my site mybibleversion.com and/or my book What’s in a Version?.) On the other hand, the NRSV is quite formal/literal while the Revised English Bible is quite functional/dynamic, yet the committees involved are from mainline denominations and thus more liberal. I recommend choosing your three translations to represent different theological traditions and different styles of translating. For protestants, I’d recommend including the New American Bible or the New Jerusalem Bible, which are translated by Catholic committees. The NAB is probably a bit more literal/formal than the NIV and the NJB is dynamic/functional like the NLT or REB.

- Instead of spending your time looking for glosses to Greek words in a concordance like Strong’s, spend more time studying relevant passages in English. Don’t find a gloss and then force it into all the verses. Rather, study each passage and look for definitions from the context. I mean definitions of the English words provided by the English context in your English Bible. So if you want to know what the “church” is, don’t worry about the definition of ekklesia in Greek. (Dave Black wrote some good notes on this the other day. If you read what he wrote about the Greek words carefully, you will see some of the difficulties in doing this sort of study unless you are very well versed in the language.) Worry about the definition of “church” (and related terms like “body of Christ”) in English verses. How does Paul view this in Ephesians 4, for example?

- In order to keep from getting stuck with the work of just one committee, compare those translations. While the formal translations may be closer to the form of the Greek or Hebrew, you may not correctly comprehend what that form means. Try the options in one of the dynamic/functional versions. Then listen to the context. Many, many misinterpretations are produced by deciding what a word in the original language is suppose to mean and then forcing the verse to fit that meaning. Ask instead whether the definition you have in mind truly fits. In English, for example, the word “car” might refer to an automobile, the part of an elevator you ride in, or one element of a train. You wouldn’t take the elevator-related definition and force it into a passage about automobiles, would you? Don’t do it to the biblical text either. Consider words like “salvation,” which may refer to a moment of new birth, a continuous process of God’s work in the believer, or the eventual salvation from final death, among other things.

- Don’t be afraid of surface reading. Surface reading is a good starting point for study. I like to read an entire book of the Bible through before focusing on a section. That’s harder to do if we’re talking Isaiah or Ezekiel, but for most of the New Testament it’s not that hard. It’s a bit like standing on a mountain looking across a forest before trying to hike through it. You can read rapidly and you don’t need to understand everything. That’s what your later study is for.

- Don’t be intimidated. Those of us who read the languages also make plenty of mistakes. We’re subject to all the same human biases. I thank the Lord for the opportunity I’ve had to learn and for the gift of reading the Bible in its original languages. But none of that work gave me the right to lord it over others or to demand that they accept my view because of my study.

Above all, I encourage you to study the scriptures for yourself and listen for God to speak to you. It is the privilege of everyone, not just of clergy or scholars. Many people have given their time and some have even given their lives so that you can have that Bible in your own language. Make the most of it!

I was given an interlinear Bible with Strong’s reference #s for Christmas. Haven’t got much into it yet, but it looks very interesting. The right to left English translation took a bit to figure out…

Strong’s has its uses. Just don’t trust it as your dictionary to Biblical Languages. It helps a great deal in discovering how the KJV translated various Greek/Hebrew words, which is a fascinating study in itself.

Just had someone in my class on Sabbath tell me they wouldn’t trust the NIV because its translated from the Catholic Douay Bible!!

I have found that there is no end to the misinformation out there about Bible translations!

Suggest you use your new bible along with others, as the article notes.

Add NIV Cultural Study Bible to compare writings, history etc. from the same – or earlier time.

Like today’s language, nothing will capture the exact same meaning as the original: and we don’t have it. Confirm this with the simplest translation sites like Google. We add our own flavour.

I have a review and some notes/pictures on the NIV Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible: Review: Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible – Hebrews and NIV Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible. The second includes some pictures.

I participated in the blog tour following the release, which is why I commented specifically on using it to study Hebrews.