Unity, Diversity, and Confusion

Recently I wrote a couple of entries, first on diversity and liberalism, and then on the Together for the Gospel statement. The issues I discussed in those two posts raise quite a number of questions about truth, unity, and Christian fellowship. Many might decide from my comments thus far that I don’t care about truth or correct doctrines at all. But that is not the case. “Doctrine” is simply teaching, and we all have some form of teaching. Even the doctrine that correct doctrine is not primary in salvation is itself a doctrine.

Where are the boundaries where disagreement is permissible or not permissible? How can we tell what is essential and what is not? It’s easy to quote St. Augustine, “In essentials, unity. In non-essentials, liberty. In all things, charity,” but it’s a great deal harder to define precisely what one means. Two sincere people who accept the idea of unity in essentials and liberty in non-essentials can nonetheless get into quite a fight over just what is essential.

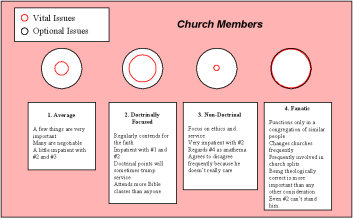

I think we could view the situation as a sort of continuum.

| Unity by Exclusion | Unity in diversity | Disunity by confusion | |

| Doctrinal | Non-doctrinal | ||

To the far left of this spectrum (no left-wing/right-wing implications intended), we have those for whom doctrine is central and absolute. I’m seeing the folks who wrote the Together for the Gospel statement I discussed in my post Who’s Together for What?. For them the way to defend the gospel is to be both very clear and detailed on what is truth, make sure people know it, and only respect those who are fully on track as bearers of the gospel. In the center of this continuum we have those who have a small number of essential doctrines on which they require unity, but outside of that boundary diversity is permissible within the community. On the far right of my continuum, we have those who hold nothing, or almost nothing, as essential, and thus have confusion because they are not defined as a community. Even greater confusion results when a community cannot agree on just where they stand.

Let me provide an illustration from another article I’m working on that looks at the type of people who might be part of such organizations:

Click the image for a larger view

Churches that attain unity by exclusion tend to have a large number of essential doctrines. These churches tend to split, and the people in them tend to move from church to church looking for a precise match to their desires. I am not saying that such a church cannot practice unit and cannot teach the gospel; merely that it is difficult to maintain unity in that atmosphere.

I believe the United Methodist Church, of which I’m a member, tends toward the other extreme. We tend to allow diversity in everything and require unity in nothing. We add to that a debate over where we should be allowing diversity, what is essential, and what is not.

the-methotaku made a great comment on my previous post, Liberalism and Diversity, in which he started to do precisely what I had planned to suggest in this article–define the distinctives of Wesleyan and then United Methodist theology. Go back there and take a look.

One reason it is often hard to define the essentials is that one can’t define “essential” without asking “essential for what?” Many people are tired of denominationalism, and I am also concerned when denominations promote themselves over Christianity as a whole. I like to call myself a “Christian, who is a member of a United Methodist congregation” rather than “Methodist.” Why? Because my primary identity is Christian. I don’t think John Wesley would have a problem with that.

But in order to be a community in ministry to the world, I need to become part of a more tightly defined group. Rather than the very small number of doctrines I suggested as a definition for “Christian” I need some additional points that make one “United Methodist” rather than Presbyterian or Pentecostal, for example. When I define such items, I am not saying that these are additions to what makes me a Christian, rather, they define how it is that I am going to live my Christian witness in the world through a community.

I can cooperate with anyone with whom I can agree on the essentials for that specific mission. That means that if I am dealing with an enterprise that is broadly Christian, I can cooperate with anyone who accepts basic Christianity. When I meet as a member of a congregation for worship, I expect some additional unity, though I still can allow diversity. I could easily form a small group that would share a larger number of “essential” doctrines–essential to our group, that is.

But in each case I must try to keep these essential doctrines to the minimum required for that particular community. When I engage in charitable activity in general, for example, I don’t need to find people who agree with me doctrinally. All I need is to find people who agree that there is a human need to be filled.

It is my prayer for the United Methodist church that we’ll reduce confusion by defining what it is that we find essential and learning to live with it. I don’t know where those lines should be drawn. I would suggest two things–they should be as inclusive as possible while allowing us to be defined as a community, and we should not use what defines us as a community to condemn those who choose a different one.

Interestign discussion.

You say: “It is my prayer for the United Methodist church that well reduce confusion by defining what it is that we find essential and learning to live with it.”

This sounds like a good strategy to me. Our difficulty is that for some what is essential is INCLUSION (being INCUSIVE), which excludes EXCLUSIVENESS. As long as we’re afraid of self-definition, we will, as you suggest, continue to lack community.

At least in my experience, the minimal self-definition we tend to chose tends not to be DOCTRINAL but ecclesial-organizational: Connectionalism, The Appointment System, Apportionments, Infant Baptism. When we do hit doctrinal issues, we often do it from a negative point of view – saying what we’re not (and here in Texas we might not knwo what United Methodism stands for, but were SURE we’re NOT baptists!).

NOTE: I think in your second graphic you mean to say that the Doctrinally Focused are impatient with #1 & #3 – NOT #2 (themselves).

Your correction is correct. I goofed. It should read #1 and #3. 🙁

Thanks!

Richard H said:

By definition when we create a community that includes less than all of humanity we exclude some and include some. Inclusion can’t be an absolute. I favor inclusiveness, by which I mean that I would work toward the maximum inclusiveness consistent with community.

I agree with most of what you said. Truth is never relative, however. Just because we choose to accept and not accept certain things does not make them true or not true. If we can ever agree on what is essential, that doesn’t necessarily mean that everything that is non essential is irrelevant. I believe in vigorous debate, even among truths we may not necessarily divide over. The truth is out there.

Brett said:

I am 100% in agreement here. In fact, I think that a unity based on pretending that everything is equally true, or suppressing our actual views, is not good for community, which will ultimately fail when done that way, but is also very bad for the search for truth.

When we agree on what is essential, we are simply finding a consensus on which we can agree. Other elements should be vigorously debated.

Thank you for referring back to me!