Review of The Passion Translation Part I – The Hype

I’m dividing my review of this translation into two parts because my actual review of the translation text and the weighted chart I produced as a result is actually somewhat anticlimactic. The controversy about the translation is quite heated, and claims for the translation are quite strong.

Evaluating a Bible Translation

There are differing ways of evaluating a translation. One common way is to critique a set of passages that are of importance to the person doing the review. This is of value provided one considers both the theology of the translator(s) and the reviewer, as it can give you an idea of the theological views of the translators.

Lists of Passages and Terms

There’s a subset of this approach which is very concerned with which English terms are used. For example, does the translation in question use propitiation in certain passages.

Consider, for example, Romans 3:25, in which the ESV uses propitiation:

… whom God put forward as a propitiation by his blood …

Romans 3:25, ESV, partial

For the same phrase, the NRSV reads:

whom God put forward as a sacrifice of atonement by his blood

Romans 3:25, NRSV, partial, emphasis mine

(It is worth noting at this point that references on this blog are linked to the passage on BibleGateway.com. Bible Gateway has chosen not to include The Passion Translation in their selection. Passages from that translation will be marked TPT and accessed from YouVersion.com. Read the Christianity Today story on this removal, dated February 9, 2022.)

If your teaching of the atonement involves substantial use of the word “propitiation,” it’s likely you’ll prefer to have that word in this particular passage. When I was a first-year Greek student, I encountered this word (loosely transliterated hilasterion) in an exercise and translated it “propitiation.” My instructor informed me that I was not learning Greek so as to translate it into Latin, and that I should choose a word that would be understood well in modern English. (“Propitiation” in English is derived from Latin.)

The controversy arises when you look at how well each term translates the original. “Sacrifice of atonement” falls within the semantic range of the Greek term, but some might argue.

Let’s look at the NLT:

For God presented Jesus as the sacrifice for sin.

Romans 3;25

I think you can recognize the connection. If you were wanting to discuss the nature of the sacrifice for sin, that is not specified. “Propitiation” indicates a particular function of the sacrifice.

We take a further step with The Message:

God sacrificed Jesus on the altar of the world to clear that world of sin.

Romans 3:25, The Message, partial

This is “more different” from the ESV than the others, and certain theological uses of the passage would be more difficult with this rendering.

Now compare this to The Passion Translation:

Jesus’ God-given destiny was to be the sacrifice to take away sins, and now he is our mercy seat because of his death on the cross.

Romans 3:25, TPT, partial

Just like The Message, The Passion Translation here can annoy many of the theologically inclined. Just what are we teaching with “clear the world of sin” (MSG) or “take away sins”/”now he is our mercy seat” in TPT?

Thus we have numerous reviews that simply list issues such as this. There is a value in looking at the text in this way, though I would suggest that our doctrinal positions should be better rooted than to be ripped out by the translation of a single verse.

There are numerous reviews of The Passion Translation that take this approach. Just do a Google search on it, and you’ll find lots. Be sure, however, that you actually check the passages that are critiqued alongside other English translations or the source texts if you can do so.

A translation can be good as a translation while disagreeing with some of your favorite renderings. That’s one of the reasons preachers often choose a different translation for some passages they preach from: They’re using the one that has wording that best supports their point!

Arguing against the Translators

Another approach critiques translators.

There is a value in looking at the qualifications of Bible translators. How much do they know of the languages? What is their orientation toward the text? Do they see themselves as translating sacred texts or simply common documents in an ancient language?

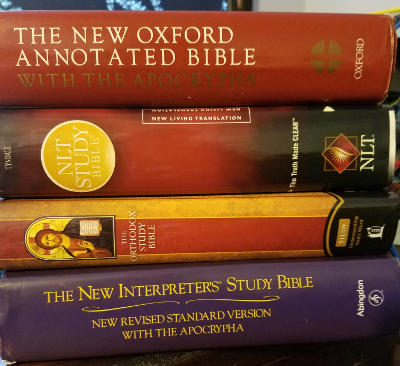

For example, in evaluating translations for my site MyBibleVersion.com, I distinguish translations according to those by individuals and those by committee, and the committee translations by their general theological orientation, as well as whether they are interdenominational and even interfaith. My purpose in doing so is that I suggest you compare translations from different perspectives.

Choosing only translations that reflect your own theological predilections can result in a skewed view of the source texts.

There is a less valid version of discussing the translators, and that is one’s moral view of them or their lifestyle. A couple of decades ago there was considerable controversy over the NIV because someone on the committee later came out as gay. I see no value in this, and a great deal negative. Evaluate the text. Don’t set yourself up as a moral judge of the committee.

My Approach Summarized

You can find a great deal regarding my approach to Bible translations in my book What’s in a Version?. That book is still available, though now a bit dated, but I still hold the same views about Bible translation I expressed in it. (Reviews of more recent translations are missing from the book, but can be found on my site MyBibleVersion.com.)

I like to start evaluating a translation as I would any book, by reading the introductory material, which should give me an idea of what the translators intend to accomplish and what they claim to have accomplished. I then try to evaluate the translation in terms of whether it accomplishes those goals.

I comment on, and readers will need to determine for themselves, just how well the goals of the translator relate to the needs of the reader. With the rich variety of English translations, we might well be looking for a Bible for easy devotional reading, one for serious exegetical study, one for preaching, and another to pass to friends for whom English is a second language.

One of the characteristics to check is whether a translation intends to present the text in a formal sense, i.e., each Greek form producing a consistent single English form or phrase, or in a functional sense. Recently, as in over the last couple of decades, translators have tended to use “functional” rather than “dynamic,” a term applied by Eugene Nida. I still like dynamic, in that it includes in its semantic range the idea of non-static. As our language changes, so would our translation.

The term “paraphrase” is generally applied to something that is considered too loose to be properly regarded as a translation. It gives a good general idea, though it isn’t precisely accurate in what it suggests.

What translation strategy you prefer will be impacted by a number of factors and convictions and goes beyond this.

A Note on Translation Accuracy

I have been asked many times which translation is most accurate. I find that a question that can’t be answered in a truly meaningful way. I can critique certain translation for missing the meaning of certain passages.

Unfortunately, “literal” or “formal” has become for some people a synonym for “accurate.” This is not correct.

Each approach to translation conveys something from the source text while obscuring other things. If you want to avoid this, learn to read the original languages. Or, alternatively, read a variety of translations.

Let me give one brief example. In Ezekiel 40-48 Ezekiel describes a vision of a rebuilt temple. He presents measurements in cubits which are round numbers. These numbers allow you to see the proportions somewhat better and might provide some key to the way certain measurements are presented in Revelation.

A formal translation, such as the NRSV, presents these measurements in cubits. How many people know what cubits actually are? Can you picture the distances based on this? The NLT thinks perhaps not, and presents the distances in modern measures with the distance in cubits in footnotes. Different information is conveyed in different ways.

Ideally, I think, someone would get both, either by having the distance in cubits in the text with footnotes giving the modern measures, or with modern measures in the text and conversions in the footnotes (as does the NLT). But that’s my prejudice. The information communicated is different with the two approaches.

Long Live Hype!

As a publisher, I’m well acquainted with hype as it relates to translations. Translators don’t decide to do new translations of the Bible because all the others are just fine and they felt like producing yet another one. They believe they have something to contribute to Bible knowledge by producing a translation that is better in some way.

This is why I like to ask what the aim of a translation was and then comment on the success it has in accomplishing that aim. It is up to my readers, or any readers of that translation, to determine whether the goal of the translation fits their needs.

If you’re looking for a translation that will let you easily relate the English content to Greek or Hebrew words using a concordance that is keyed to the languages, then you need something more literal. You don’t want to pick up The Message. You likely also won’t want The Passion Translation, because that is not the translation approach used.

Hype on The Passion Translation

The hype regarding The Passion Translation differs in one important way from that on most other translations. The translator makes strong claims regarding the divine origin of his call to this work of translation and also to specific translations.

I think a good way to get the flavor of the hype is to listen to the translator himself.

Interview with Brian Williamson by Sid Roth. (The video does not provide an option to embed.)

Let me start by listing things that I don’t object to.

- I do not object to the translator claiming a call from God to do the work. In fact, I would suggest that any Christian could and perhaps should make such a claim when embarking on a project. I pray over and consider God’s call with every book I publish. That doesn’t mean I am without error in my choices.

- I do not mind claims of miracles. I haven’t investigated these but I do not reject such things unless I have investigated and found a false claim.

- I definitely don’t mind getting translation ideas from the Holy Spirit. I’ve gotten great ideas, or at least ideas I think were great, while sleeping. These, of course, must then be validated where such validation is possible. In the case of translation ideas, they should be validated through actual manuscript and linguistic data.

I would note that I do not agree with the particular translation in Ephesians 5 that is offered in the video, nor with the reasoning behind it. I’ll comment a bit further in my next post completing my review of the translation.

A Concern

I have a concern, however, which is strengthened and perhaps made more urgent by my experience growing up as a Seventh-day Adventist. One of the concerns evangelicals have had with reference to the SDA church is whether they are adding to the Bible through the writings of Ellen G. White.

Ellen White saw herself as a messenger of God, but her writings often have exaggerated respect among members of the church. By “exaggerated respect” I do not mean that people believe Ellen White heard from God. I regard that as quite possible. I do not mean that people find her writings enlightening. I have my library of Ellen White books in my office and find a number of them helpful, despite some theological disagreements with the author.

No, by exaggerated respect I mean those who would regard Ellen White as definitive regarding interpretation of the Bible. I recall a discussion I had that involved a theology professor with a PhD in ancient near eastern literature. He expressed a particular interpretation of a Bible passage. I disagreed, and gave some reasons why I believed it didn’t fit. He, in turn, told me that “Ellen White gives this interpretation.” I told him I did not make my decisions on that basis. He expressed shock that I would not accept Ellen White as the final authority on the interpretation of a passage where she had rendered an opinion.

I was shocked myself. I had not expected someone of his skill to simply accept the word of a claimed messenger of God as definitive with regards to what a Bible passage means.

The Bible is the common source of doctrines of the Christian faith. I’m not talking here about inerrancy or infallibility, but rather of simple appeal. We go back to this source in common. (Note that I believe the formation of doctrine is much more complex. See my most recent note on the Wesleyan Quadrilateral.)

When we have either a denominationally specific or a tradition stream-specific authoritative source that tells us what the Bible means, that historical connection breaks. This is a key reason why I prefer committee translations and specifically committees that include members from various tradition streams.

If one is asked to accept a particular translation based on a message one has received from God, I suggest sticking with the source.

Now just as I can now read Ellen White as inspirational and very helpful because I don’t read her as a final authority, so I can read a variety of translations without feeling obligated to agree with any of the renderings if I find the evidence suggests otherwise.

Summary

Other than the greater involvement of references to the Holy Spirit and to miraculous activity, I don’t find either the hype or the criticism of that hype extraordinary. It is normal for strong claims to be made for a translation and for reviewers to challenge those claims.

In my next post, I’ll review the data and discuss how I view the translation as a whole. I’ll give you a spoiler: I found that the translation was much less out of the mainstream than most claims about it, and I also found that I was somewhat less excited about the way it is phrased. It falls into the tradition I would call hyper-dynamic, also known as paraphrases, and should be evaluated as such.

One Comment