Is It Greek Pedagogy, Learning Skills, or Something Else

These discussions seem to come up all the time about learning Greek, but the discussion also applies to Hebrew. How one can imagine it’s critically important to learn Greek if one is to preach or teach, but not so much to learn Hebrew, I don’t know. But the degree requirements of various colleges and seminaries reflect just such an attitude.

That said, I want to make some comments about learning and teaching, but more importantly about goals. Thomas Hudgins has written a good deal about this in a recent post, and he posted some material from Dave Black, which provides me a good link for that as well. Both make some excellent comments on pedagogy and what those of us who teach need from the students.

On the use of the word “we,” I want to note that my role as teacher is vastly different from Dave’s or Thomas’s. I tutored Greek as a student in graduate school, helping Master of Divinity students get ready for tests. And that was indeed what it was: Getting them ready for the test. None had patience for letting me help them comprehend the subject better. They wanted to make sure they had memorized enough answers to get by on the test. Since then I have occasionally offered classes in the local church or tutored individuals who were trying to learn. The key element here is that people came to these classes because they had a goal, and they pursued the goal.

And this is why I think we need to look at two other things. I used “learning skills” in the title, but what I really mean is the art and practice of being a student. There’s probably a perfectly good word for it, but short of suggesting you be a good talmid, I can’t bring it to mind. But beyond learning skills there’s motivation, and behind motivation there’s purpose, or perhaps mission.

That leads me back to graduate school and my graduate advisor, Dr. Leona Glidden Running. I was truly blessed to have Dr. Running as a teacher and advisor. I learned enormous amounts from her in classes in Syriac (which I audited), Akkadian, and Middle Egyptian. From the list of languages you can see that I had the motivation for learning languages. Thus I learned from good teachers and some whose pedagogy may have lacked a bit.

It was also Dr. Running who got me into tutoring and sent her students to me for help in both Greek and Hebrew. The problem with tutoring points me to what I think is a problem in ministerial education: Students going through language courses in order to check a box. We’re often fairly good at ditching traditions in Protestantism. Just look at the reformation! But folks, that was 500 years ago. What traditions have you ditched lately?

What I encountered were students who were studying Greek because it was required for the degree, some of whom had been told by ministerial advisers, mentors, and church leaders that the only reason they should learn Greek was to get their degree, and most of whom would serve churches that didn’t care what biblical languages they might have learned. Is it any wonder that they just wanted me to help them through the test? I can’t count the number of times I was called within hours of the test, or late on a Friday afternoon or even working into Saturday with desperate pleas for that help. At this time I was a Seventh-day Adventist and I took my Sabbath seriously. (I’ve recently commented that it’s one thing from my SDA background that I really miss.) But these ministerial students who were supposed to be preparing to shepherd people in that tradition, were quite ready to ditch their Sabbath rest to get past the test.

I know from reading what others have said that while the details may differ, the attitude is quite similar. Some seminaries have given up on the languages as a requirement. Often those seminaries are ones that have reduced the entire biblical studies requirement to a minimum. So study of biblical languages goes the way of Bible study, and it all happens without that much planning.

So speaking as someone who thinks biblical knowledge is critical, let me suggest that we need to reexamine this entire process. What is a Master of Divinity degree for? What are our goals? Within that, what are the goals for knowledge of the Bible? Of biblical languages? Once we know what we need—and want—then we need to ask how we get it. Forcing students to take one or two (or whatever number) of semesters of Greek and/or Hebrew doesn’t accomplish anyone’s ultimate goal, at least anyone I know of. Nobody actually hopes that the student will pay tuition, check off a box, and leave with no knowledge that he or she will use (except possibly the university finance department).

I don’t know about other biblical languages classes, but my teachers taught with the goal of having us learn to read the language. They knew they were only going to accomplish that in a few cases, but they still worked toward that goal. If the assumption of everyone else is that the student will not, in fact, learn the language, then we need to do something about that. That isn’t something that a Greek teacher can fix. He or she can try to motivate more students, to provide as much useful information as possible, but that all constitutes making the best of a bad situation.

Amongst the possibilities that should be considered are requirements for additional classes in history, cultures, people (sociology/psychology), linguistics, or other topics that helps a person understand a written text. Perhaps, in addition, one might include classes specifically in taking complex ideas and expressing them clearly and simply (to whatever extent possible). Then we can aim the biblical languages classes at people who do actually want to learn to use the material.

I have to put in my ritual dig at the whole educational system. I think that in the 21st century world the degree system is getting more and more out of date. Something more like the badges system that the Mozilla Foundation is sponsoring may be at least an early pointer toward a replacement. But that moves beyond this post …

In summary, in languages as in anything else, we need to keep our focus on the mission. That starts with knowing what the mission is.

And we don’t.

You are right on target with your question. What is the motivation for learning these ancient tongues? As background – I was taught Latin as a child at the end of a stick – the stick being used to beat the subject into us. Only when the abuser was removed from the scene did I meet someone who suggested we learn to read the tongue. At age 16 and leaving that school, it was too late for me. But I retain the drills – amo amas amat, etc. I have always found language difficult, but with French and English in my pocket, I found picking up snippets while traveling OK, but they are quickly forgotten.

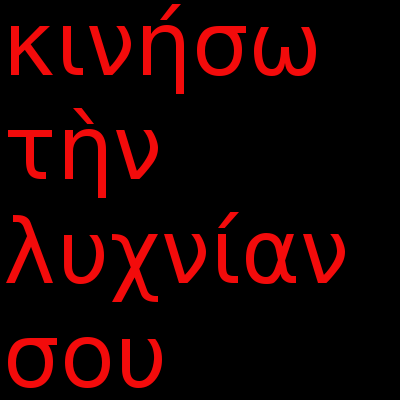

Much later in life, I began to learn Hebrew, as if it were my childhood tongue, just bearing with study and application, at first just 15 minutes a day, reading the OT. Why? What motivation? Because this is the tongue in which my Lord learned his own work. And whatever the cost or difficulty, I follow him. What I find is that the lenses through which we read the ancient texts are very dirty, covered with the accumulated rote learning and theological bias of the past 1800 years. It is impossible to see clearly the tradition that carried this Word to us if one is only reading in translation. I hate to say it in this way for fear of being misunderstood. It is not impossible (of course) to hear the Word in any tongue, that living voice in us that teaches and admonishes us. This is everyone’s gift, but if one wants to help clarify where we are as the people of God and where we’ve been, one has to question all the distractions that give us trouble. It is curious to note this about Hebrew: word, matter, thing, and pestilence can each be seen in one Hebrew root – d-b-r or דבר. Will you have a word דבר from this or a pestilence דבר? The word in this form occurs twice in Psalm 91, perhaps one of our favorites.

Now you might ask, Did Jesus really have to learn from the Hebrew text? Didn’t he know it already? Didn’t he have a ‘direct line’? We read in the letter to the Hebrews that he learned (Hebrews 5:8). He is not as son, superhuman, but fully human, in all points like us. And in the same letter, we read the dialogue between the Father and the Son – and this conversation is taken from the Psalms – so how important are they for our growth? And how best should we read them? Well, you know that ‘direct line’ is the wrong metaphor. The heart simply needs to turn, and that’s what the Psalms teach through that inner voice that simply needs to be heard.

And would you learn Hebrew or Greek first? I have started with Hebrew in part for the reason given above. I have not studied Greek though my Latin helps me in understanding it. But since learning Hebrew, reading Greek reading just seemed to happen. I have no explanation for that. It is not a short process and I have taken no exams except as the Lord has delivered me into certain situations that required my jump to the next step. I also have felt free to ask any question of the text and its interpreters over the last millennia. The resulting study of history and tradition has been revealing.