Why I Still Like the Wesleyan Quadrilateral

Yes, I’ve heard the complaints, and those who say it isn’t actually Wesleyan or has deteriorated through the years, but I met it in the United Methodist Discipline before I first joined a Methodist church (though without the name) and I still like it.

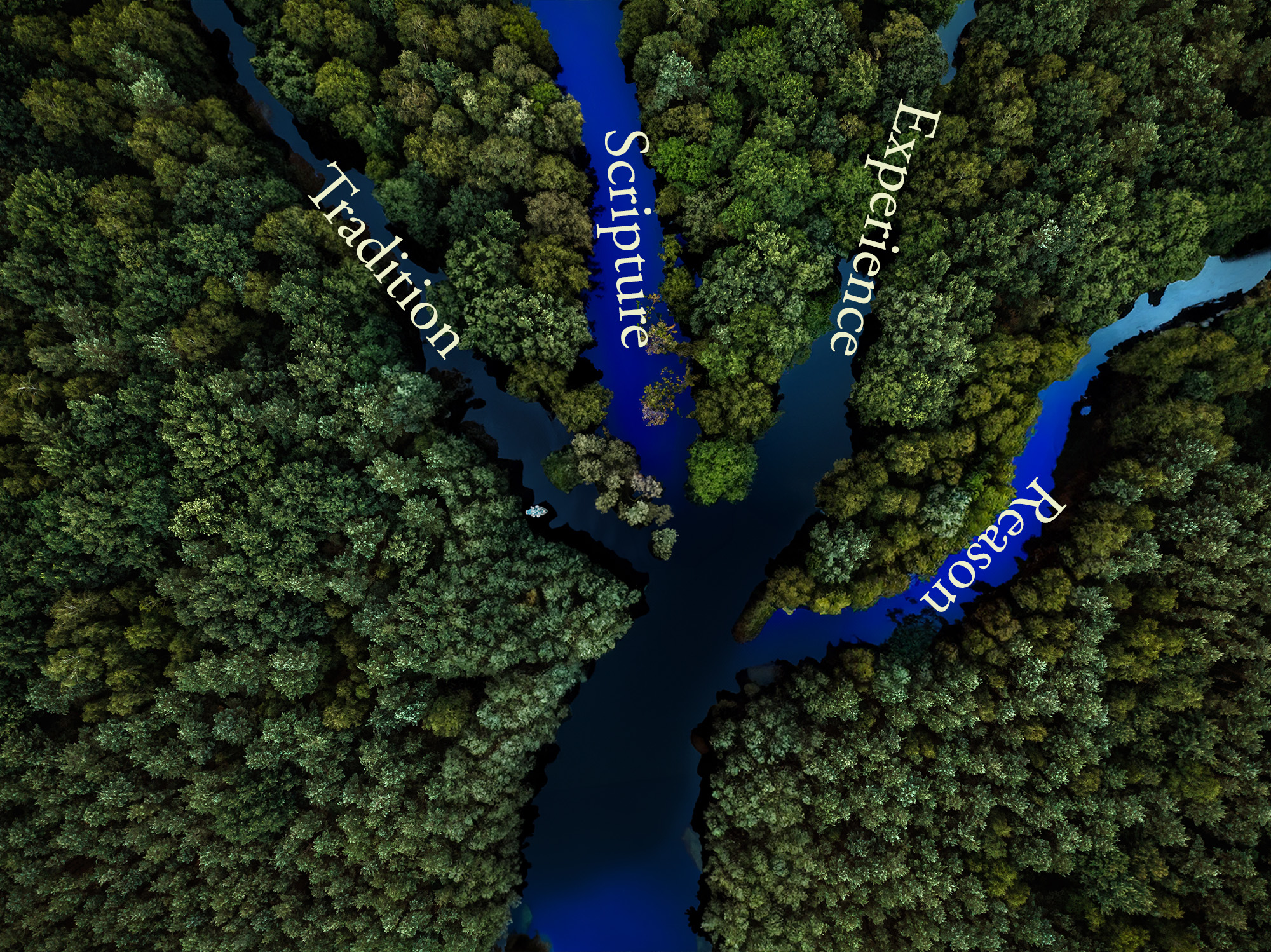

For those who may not be aware of the quadrilateral, it states simply that doctrine is formed not from scripture alone, but from scripture, tradition, experience, and reason. (I discussed the importance of experience in a 2015 blog post.)

On this blog, I have discussed this several times before. Today I want to add a metaphor and expand a bit on the hermeneutic that I use as a result. As I have noted before, many intractable arguments result from discussing conclusions from scripture without discussing hermeneutics, the way in which we come to those conclusions. The other person may seem obtuse to you, but if you understood how they are coming to their interpretation, you might understand their point of view. You also might still abhor it, but you’d understand it!

The metaphor I want to introduce here is the confluence of four streams. This metaphor uses “confluence” to suggest the way sources interact to help form doctrine.

To help clarify this and its purpose, let’s start with its opposite. For many, scripture is a fixed source of data. You go to it, mine the data, and then directly apply it to your life or the life of your community here and now. We should have learned from the experience of the Christian community that it doesn’t work that way. Thousands of denominations and various church splits, carried out by people who thought they were (and generally think they are) faithfully following the Bible should have given us a clue.

The nature of scripture itself should give us a clue. It is not organized as a compendium of knowledge. It is not organized like an encyclopedia, or like the Boy Scouts Handbook (a metaphor I’ve heard frequently), nor like the more modern FAQ page. It’s a collection of a variety of material produced in a variety of ways, organized and presented differently, and then collected and placed in one volume. Out around the edges, various of those denominations disagree on the details of what should be considered part of the Bible.

I have this feeling that God accomplishes what God sets out to do, thus when I see a Bible that looks almost entirely unlike what so many people want it to be, I come to suspect that God didn’t want what they want. If God had wanted that, it would be what we have. We don’t, so God didn’t.

I recognized the problem back in 1993 when I was considering a return to church after about a dozen years, but I didn’t have the vocabulary to express it. For a number of reasons that seem to me providential, I visited what was then Pine Forest United Methodist Church (now Wilde Lake Church), and generally liked what I heard, but I’m an idea-driven person and I wanted to know what these Methodists believed. On being asked, the pastor thought and finally handed me a copy of the United Methodist Discipline.

As I read that document (the first 100 pages or so, not the organizational stuff in the back!) I encountered the description of what is often called the Wesleyan Quadrilateral. I loved it. Not because I thought it was a good prescription for how to do Bible study, but because I thought it described how people study the Bible.

We bring to our study what is in ourselves, such as our observation of the world, our thinking about various things, our experiences with others, our knowledge of past events, things we know work for us, things we know do not work, and our relationships or community, in whatever shape that community bears.

The simple explanation for why our interpretations differ is that we differ. Those differences are not just in us, but in the way in which we are connected to others both in space and in time. These are not things we can escape; they are part of us.

The Bible looks a great deal like it was produced by people much like us.

Do I mean by this that there is nothing special about the Bible or that there is no divine inspiration involved? Not even a little bit! What I mean is that I see Divine action in a community of people that stretches not only through space around the world but also that stretches through time. It is a diverse book delivered through diverse people who lived in diverse communities to a wide diversity of other people and communities across the span of time.

Does this mean that I can learn nothing from the Bible? Not at all! What it does mean is that I can’t reach into the Bible and grab a rock to throw at you or at anyone else, and truthfully call the rock “divine.” And I think that’s a good thing. Possibly even a Divine thing.

As I was thinking about all of this, I was also looking at some pictures of river confluences (if anyone cares, along the Essequibo River in Guyana and its tributaries), and I thought, “A confluence of four streams comes closer than anything else I’ve thought of to the way the quadrilateral actually works!”

Of course, there’s nothing quadrilateral about this metaphor. Well, except the “4” part.

Let me note what I see as the problems of the previous metaphors, especially my own. The whole “quadrilateral” metaphor tended to make four elements equally authoritative in forming authoritative doctrine. In many ways, we’re still looking for that rock to throw, but we want its authority to be derived in a different way.

My own response with the four-layer filter, in which I suggested that a doctrine should be tested by all four elements, suffers a similar problem. I don’t find it entirely unuseful, but as with many metaphors, it needs a “don’t stretch” warning label. My metaphor of the four-lane highway, a critique metaphor, similarly starts with our hoped-for conclusion and then tests it against the four, in this case looking for a lane that will work.

The four streams metaphor suggests several things, including that the streams keep flowing. They are not actually static. The water in the stream that results is a mixture of all four, which may vary by season, situation, and geography.

Is any of this safe? No, but nothing is safe. Doctrine is not a static object that exists outside our community. It is formed in community, practiced and taught in community, and it belongs to the universal church, not to you or me personally.

This does not make me take the Bible lightly. In fact, it suggests to me that I need to immerse myself in scripture and also in my community of faith in order to be guided by the God who guided the community over time and continues to guide it and me. No superficial glance intended to prove myself right and someone else wrong will do for this.

We embrace a diversity of interpretations that fit within the streams that meet at the confluence to produce doctrine. It is a continuing journey, along with that “great cloud of witnesses” led by Jesus, the “author and finisher.” (See Hebrews 12:1-3 with reference to Hebrews 11.)

2 Comments