Translation, Exposition, and Communication

Yes! I have found another pretentious title for a relatively simple post!

I’ve been following the discussion around the blogosphere about literary translation, which has involved any number of blogs. I’ve been too busy to write about it. I was about to start last night, and then Doug at Metacatholic said part of what I wanted to say, and I waited until this morning to put it all together a bit more.

In working with secular literature, and even with much religious or spiritual literature, there are many ways in which a work can be transformed to reach a particular audience. One of the methods I’ve been playing around with is simply writing a very short fictional piece that tries to teach the same lesson (example here). The point here is not to produce professional fiction or for the teacher to produce a “better” story, but rather for students to study the story by changing its form. I would ask students to tell a story from their own lives or to create a fictional one to teach the lesson. In studying Bible stories I also use the technique of having students tell the story from someone else’s point of view (see the section toward the end on Ahab’s Viewpoint).

In secular literature we can have a book re-presented as a condensed book, a movie, a play, a children’s edition, illustrated edition, modernized (for an older work), and so forth. In each presentation, there are many choices made in terms of what of the original work will be presented again and what will be left out. Any time one changes the presentation, one loses something, and one may also gain something. The person who alters the form may well instill some additional meaning into the work that was not there before.

But in Bible translation it seems to me that we tend to operate in fear of doing it the wrong way. Now don’t get me wrong here. I have very strong preferences in terms of Bible translation. I’m an advocate of dynamic equivalence, and of using ordinary, natural expressions in the target language. That is what I want most in a translation. If you think about it, and then realize that the most common thing I’m doing with a Bible translation is using it in a teaching context, you will realize that my preference of translation and my purpose tend to line up. One must add that I do not pretend to teach my classes Greek or Hebrew (unless that’s the subject!) and thus I am uninterested in a presentation of the forms of the source language.

Nonetheless, as I talk about translations, I tend very strongly to speak in terms of lines of division. There are formal equivalence and dynamic equivalence, and never shall the twain meet. Now I actually believe there is a continuum (illustrated here), but that continuum easily gets lost in discussion.

Let’s take [tag]The Message[/tag] for example. The key question people ask me, and the one I’m likely to bring up if they don’t, is whether this version is really a translation or not, and whether it is “good to use.” I can then analyze the language, and how close it is to the source, and in general I must admit that The Message doesn’t seem to me to reflect the original very accurately in many cases.

But let’s shift context. Would I say the same thing about [tag]Eugene Peterson[/tag]’s teaching or his exposition in other material that he has written? There’s a bright line there that we may not always acknowledge. If he’s expounding, it’s OK. If he’s translating, well, not so much. What we are generally looking for is a solid line that divides working with the original languages from translation, and then working with a translation from someone’s exposition.

But is such a line realistic? Let’s compare my reading of Hebrew, for example, to that of a Rabbi who has spent his entire life working strictly with the Hebrew text. Alternatively we could compare my reading to someone who has spent his entire life studying comparative ancient near eastern languages, which is closer to my own study. Since I went from that study at the MA level to teaching Bible at the popular level, I have spent a great deal less time in the details. I would expect there to be points that either of those experts would see in the text that I would easily miss. When I read their expositions, I see this in action.

Let me belabor the point a bit before I build on it. I had read Leviticus through in Hebrew several times on my own, and done so in connection with Nahum Sarna’s JPS commentary, for example, but then I picked up Leviticus with Jacob Milgrom’s three volume Anchor Bible set. I claim to study from the original languages, and I do–in a sense. But not like that!

On the other hand I regularly encounter preachers who say that they prepare their sermons from the original languages, and yet can barely work through the material word by word. Now don’t take this as criticism. I congratulate them for using all the tools at their disposal, but their specialty and their calling doesn’t allow them to become experts in everything.

Hopefully that portrayal will do to show three levels of reading of the source texts–the expert in the texts, the person with facility in the language yet who does not professionally research on linguistic issues, and the pastor/teacher who knows some of the language. Anyone with experience could fill in the blanks either direction.

We could similarly work our way through a continuum of levels of study with various English translations, based on how accurately the text conveys the maximum possible content of the source text. Somewhere in there we should fit someone who studies from multiple English versions.

Finally, if we keep looking, we’ll find those persons who really don’t learn directly from the text or a translation at all, but rather learn the Bible in their community through exposition. There is a contempt in conservative Christianity for such people, but there are many who do know their Bibles quite well simply because they are regularly in the church when the scriptures are read and expounded, or they get similar knowledge from reading. This kind of thing makes folks like me nervous, because there are plenty of written materials that I believe distort the meaning.

Now note that the continuum I have presented is based solely on comprehending the intended message of the text. If I were to abandon that particular question, I might ask instead what methods of study and exposition result in the greater absorption of the spirit of the text by the students. That would result in quite a different list.

I could again shift views and try to build a continuum based on what produces a community sense of worship in reading scripture. This is a tremendously neglected area in many protestant churches. The information content is the sole criterion. The notion of the scripture reading as a vehicle for community worship is rarely considered. I can evoke cries of dismay when I suggest that respect for the scriptures might well be enhanced by reading all four lectionary texts on a Sunday. There seems to be a sense that if we don’t talk about it, if there is no sermon that builds directly on all those texts, there is no point in reading them. That comes from the idea that only knowledge is important.

When reading scripture for worship, the literary quality of the text becomes more important, and especially the sound of the text when read aloud. Out of modern versions I like the sound of the [tag]New Jerusalem Bible[/tag] or the [tag]Revised English Bible[/tag] in public reading, but I know a number of people who would still go for the [tag]KJV[/tag] solely for its literary beauty. Now I don’t happen to like the KJV all that well myself, but I believe that literary taste has only a small objective portion and a very large subjective portion (a few notes on this here).

If I were to work solely from my own tastes, I would suggest trying to match the literary quality of the original in translation. If so, [tag]Hebrews[/tag] should be harder to read, even when you know all the vocabulary words, than is [tag]1 John[/tag]. But of course it should not merely be harder to read; that’s just a product of someone not steeped in the language and rhetorical techniques reading a rather sophisticated text. The translation would need to be a literary masterpiece in English. My question would be this: Can you do that without reorganizing the material? In order to present the message of Hebrews as perhaps a masterful short theological essay, would we not need to take liberties with the structure of the book? After all, few English readers even notice the various literary features.

What I’m suggesting here is that none of these issues are binary issues, and that there are very few absolutely right and wrong answers. I use the slogan “the best Bible version is one your read.” My point is that different people will be comfortable reading, and will understand different Bible versions. There will always be a compromise on what is conveyed and what is filtered out by the translation choices. That is simply a feature of translating, transforming, or expounding a message.

One last note for those working on single translations into languages that are likely to have only one. There I can think of no better goal than “clear, accurate, and natural.” It’s very easy to set goals that are out of range of human thinking. In English, where so much effort is expended, we have the luxury of using multiple version and thousands of books of exposition to get the message across. In languages much less privileged–or abused–that doesn’t exist. There I would have to say that having something clear, accurate, and natural would come before anything else.

I sense that understanding in Peter Kirk’s post “Literary Translation” and Obfuscation, which I think brings up a number of points. Look at that post from the perspective of a Bible translator who is not adding yet another English translation to the literature.

Let me note the following from John Hobbins: Is Literary Translation Possible and If a text is literary, its dynamic equivalent in translation must also be literary From the second I take the following:

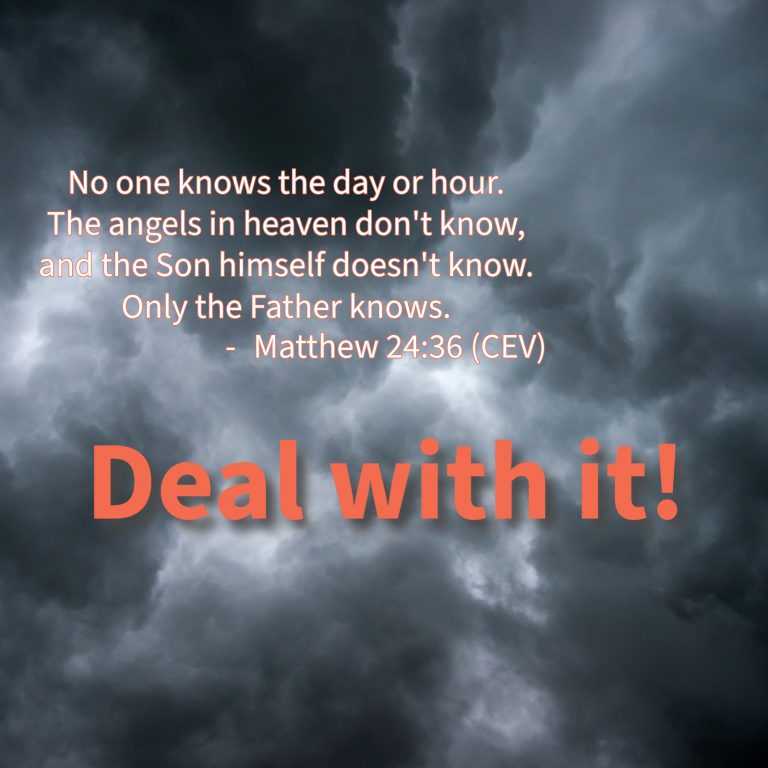

But that means that dynamic equivalent translations like the Good News Bible and the Contemporary English Version are improperly done. For vast swathes of the Old Testament, the translation they offer is not literary enough.

My point would simply be that I don’t accept the phrase “improperly done.” They are done according to the goals of their translators. The proposed “literary” translation would not accomplish that goal. Let me belabor the point some more. I love reading the [tag]REB[/tag]. It sits open on the reading stand by my computer because I love to consult it. I love to read it aloud. But I cannot use it in teaching, because I end up with too little understanding of the text. What to me is literary beauty obscures the meaning for them.

For my goals in teaching, the REB is “improperly done.” But for my goals in reading and study, it is quite “properly done.”

Thanks, Henry, for joining the conversation.

I agree with you that translations like GNB and CEV accomplish what they set out to do, which does not include offering an REB-like translation even when the original language text translated, for example, a psalm like 51 which I have been treating, is as literary as REB is.

GNB and CEV deliberately translate at a lower level linguistic register than that in which the source text is written in the case of the Psalms, Job, and so on. My point is that in so doing, the translation offered is dynamic alright, but not equivalent.

Thank you for your many helpful contributions to the study of the Bible.

And I could hardly disagree with you on that point. I think, however, that one loses one or another variety of equivalence, no matter how one translates.

I must note also that I like your Psalm 51 translation. I may comment on it further later.

A minor nitpick: the JPS Leviticus volume is edited by Levine, not Sarna (he did the Genesis and Exodus).

Good catch. I read all five in order and must have had Sarna on the brain! Or at least I’ll use that as an excuse.

More likely it’s write in haste, repent at leisure!