Sunday School: Thinking about Sacrifices

I’m preparing to teach tomorrow, and the main text is Hebrews 4:14-5:10. The quarterly is kind enough to stop just before the author tells his readers/hearers that the topic is difficult and they’re not very bright!

Nonetheless, the idea of priesthood brings up the idea of “sacrifice” and “sacrifices,” and these are two concepts that I don’t believe modern audiences are prepared for. We tend to get locked into one of two unhelpful modes.

On the one hand, we may believe sacrifice is critical, and its primary, or even only purpose is to atone for sin. This feeds into the penal substitutionary atonement theory (or I prefer metaphor), in which the sacrifice of Jesus is specifically as a substitutionary death taking the punishment for our sins. The reason I prefer metaphor to theory here is that a theory should be an explanation that deals with the relationship between various facts. A good theory is a singular thing because it is the best explanation of the data. A metaphor, on the other hand, is one of many ways of looking at a set of events. In this sense I reject a substitutionary atonement as a theory, but accept it as a valid metaphor.

On the other hand, because the whole idea of substitutionary atonement, sometimes even referred to as “cosmic child abuse,” is so foreign to our way of thinking about things, that we reject everything that relates to it. But there is a least one really good thing about substitutionary atonement (and I believe there are others): A person convinced that Jesus died as a substitutionary sacrifices for his or her sins will be convinced that wrath and punishment have been averted.

This is not the place to cover this in detail, but I am doing so in my video series on perspectives on Paul. I started in Paul’s Gospel vs. Another Gospel, then went on to part 2, and this coming Thursday night I will be doing part 3. I’m thinking there may be yet more parts, because I’m looking verse by verse at some defining statements about the gospel in various Pauline and disputed epistles.

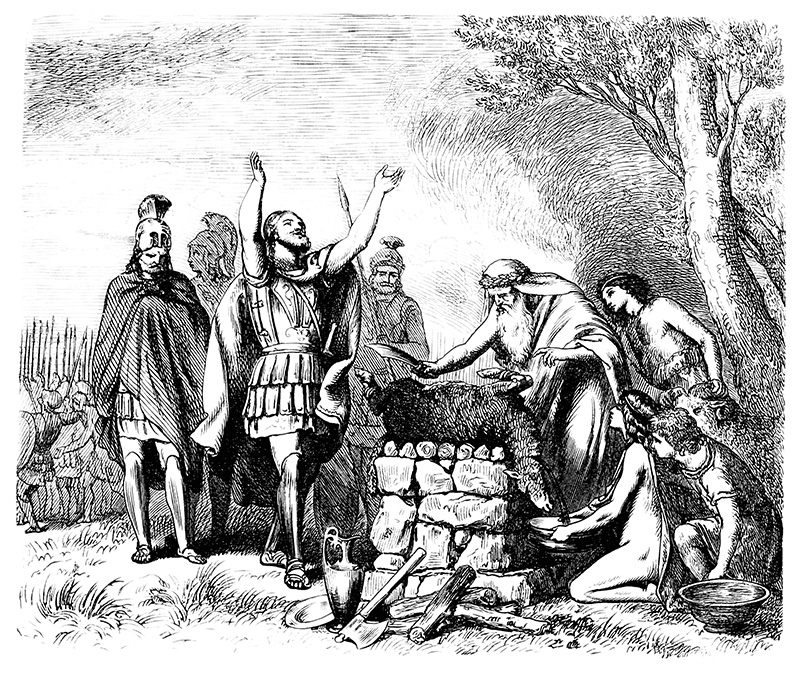

I think there’s a better background against which to think about sacrifice, and that is communication within a relationship. The priesthood and sacrifices were part of the way in which ancient people carried on communion within an ongoing relationship with their god(s). The Israelites had specific ways of offering various sacrifices, ways of representing their God, and expectations.

I like to think of gifts that I give my wife. One of the traditional gifts for someone with whom we are romantically involved is roses, often a dozen, maybe two dozen. I have only done that once in our relationship. I mean the dozen. There have been a scattered number of times on which a gift has included roses, but that is much less frequent than in other relationships.

So am I neglecting my wife and being unromantic by not giving her the traditional gift? I don’t think so, and she’ll surely read this post and let you know if I’m wrong. We’ve established a different tradition that fits her personality and mine. That tradition has to do with surprise and variety. I look at various places where I can buy flowers. The grocery store even works out frequently. I look for flowers of a different color or a different type than she has had recently. I often buy enough for a couple of arrangements in vases. More importantly, I try to bring the flowers into the house when she is not expecting them.

It is true that flowers are frequently a way of expressing regret for a wrong action, but that wouldn’t work all that well in our relationship. In fact, the only thing that does work is sincere regret, directly expressed (no weasely political apologies), and a discussion of how we can improve as we move forward. Flowers as a sacrifice for sin are not functional in our relationship, yet they are given.

I’d like to suggest thinking of the reason why you might do something for another person, or have something done for you and the various reasons you might give or receive a gift. Then start looking at the sacrificial system again. There are still many things that will not connect. For example, in those cultures that practiced human sacrifice, the killing of the human victim—the ideal one being a firstborn son—was seen as giving that child to God. So also with the animal sacrifices.

If you think of the sacrifices in this way I think it will be easier to follow how sacrifice was replaced by the “mitzvah” (good deed) in Judaism, and by a combination of giving and symbolic acts in Christianity. You might even start to think about the Sunday liturgy at your church and what it says about what God would like to see happening in your relationship to him. Is it possible God might prefer a “mitzvah” of some sort?

I’m going to build on this, but I think this is a good foundational metaphor to use in looking at sacrifice. Then we can adjust for the people involved and how they viewed what was good and bad in a relationship.