Finding an Authoritative Translation – Supplement A

In my entry Finding an Authoritative Translation I talked about ways in which a person who is not familiar with the source languages can nonetheless check for translation problems and at least be forewarned as to where translation may become an issue in Bible study. I indicated I was going to go back to talking about inspiration, but first, I need to correct a couple of oversights.

I left the New English Translation (NET) off of my list. It should be included under Literal, Protestant, and Evangelical. While the translation will deviate somewhat from a fully formal equivalent translation, that is still its primary philosophy. (This is reflected in my detail page for the version, which shows a ‘9’ for the formality on a 1-10 scale, but also a moderate ‘5’ on functionality.) Don’t read anything into my missing this translation on the previous list. I don’t include it reluctantly, and I didn’t even get an e-mail from anyone telling me I forgot it. I just plain left it out, and it is one I use regularly in comparing translations.

Secondly, thinking of the NET reminds me of the use of footnotes. Supplement all of the other procedures I mentioned with checking the footnotes of each and every version that you use. Translation footnotes are a good indicator of both the level and difficulty of the translation issues involved. To see this in action, when comparing a verse through whatever set of versions you use, make a little checklist of which versions have a footnote related to the issue you’re researching. If you find that practically all versions have a note, this is a probably a question that has caused widespread discussion. Divide the notes as well as the chosen translations into a groups according to how they solve the problem. How many different types of solutions are there to whatever question is involved. This can be considerable work, but at the same time, there’s a great deal of information contained in those brief notes.

In using all of these versions and footnotes, be sure to check the front matter of your Bible edition for information on how the notes are formatted, and what they may contain. They are normally explained there, and you will get more from your Bible edition if you know how its features work.

This may leave some folks with the question of why the notes in your Bible would vary so much between one translation and another. I think this relates directly to the more common question of why Bible versions differ in the first place. The process of translation is one of making choices. As I said earlier, no translation is perfect. The translation team must make choices of text, wording, style and so forth. But they also must make choices as to what is important enough to put in the footnotes. Too many footnotes can clutter up the translation and make it hard to use; too few may leave the reader without needed information.

Before you get upset at one or another translation team over the number of notes, consider these issues. It’s easy to make a translation for yourself that you like. (It’s interesting that Suzanne McCarthy on the Better Bibles blog made some comments about personalizing a Bible translation. I wonder how that would work!) When I make a translation for my own use in study it will very from slavishly literal where I might want to reflect a source language idiom, to extremely loose where I think a difficult point needs to be clarified. An ordinary reader would find this a very frustrating translation to use, but it suits me just fine. It’s much harder to make a translation for a broader audience, and there have to be trade-offs.

Two caveats:

1. Beware of translation shopping, by which I mean going from version to version until you find one that has the right wording. Some people go so far as to search concordances for different versions to find the wording they need to make a point. If the reason you choose the wording is that it is clear, and that it brings out what you believe to be the accurate meaning of the passage, that’s a good thing. But if you have simply sought words that work in some particular sermon or illustration, then you may be taking the text out of context.

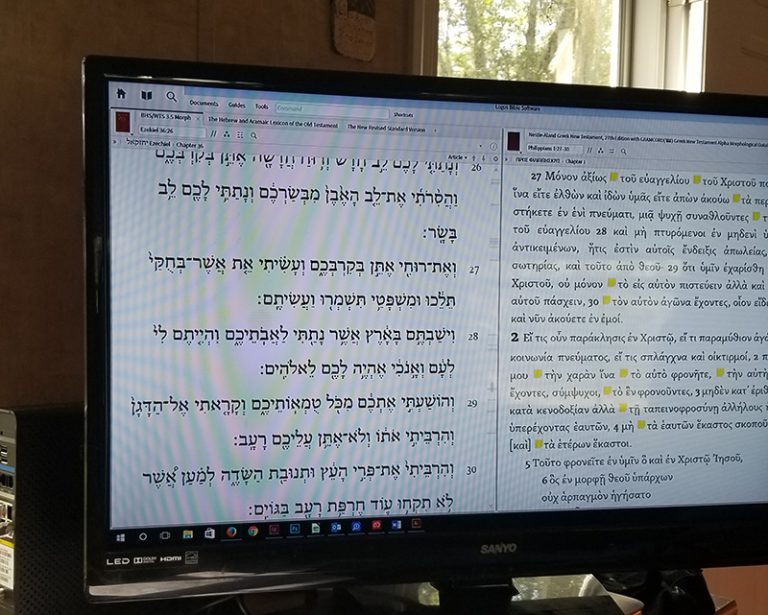

2. Beware of “what the Greek or Hebrew text really means.” I really abhor hearing this phrase in a sermon, because it will almost always be followed by misinformation, or at least information that is slanted. As I noted above, translation is a process of making choices, and what normally follows “what the Greek really means” is the gloss for that word that best suits the topic of the preacher’s sermon. I’ve had several years of training each in Hebrew and Greek, and then significant experience teaching directly from the Biblical languages, and I can’t even begin to produce the quality of translation that an expert committee can produce when translating on the fly, or in sermon preparation. I know there are people with better Greek or Hebrew skills than I have, but I suspect most of them would not claim that their off-the-cuff translation would be better overall than the work of a translation committee. What I’d suggest saying is something like this: “This verse could be translated _______” or “Another way to look at this verse is _______” or “The connection of this verse with our topic might be clearer if we translated this as ________.” All of these allow the speaker to focus on the application of the verse to the particular audience and to suggest an alternative translation, but do so without suggesting to the congregation that the translation in front of them is wrong, and that their pastor or teacher is capable of correcting it in the course of a 20 minute sermon.

None of which means you can’t suggest that one translation is better than another. Just make sure people know that translators can honestly differ, and that the versions they have before them were generally produced by dedicated, skilled people.

I was being a little facetious really. Sorry. But I did like what I read of your book – the first few pages – very much. My problem is that I started reading Greek at 14, before theological distinctions became important to me so I don’t know what it would be like to want an authoritative translation. My older sisters also studied Greek. Up until the beginning of this century, many men and some women studied Greek in high school, as college prep.

This century is an anomoly. Especially in English speaking America. Greek and Latin were taught much later in Quebecand Europe. It just happened that there were two Christian women in our school in Ontario who taught Latin and Greek. One retired and became a minister, the other stayed on to teach. I was one of her last Greek pupils.

I know you were being facetious, Suzanne, and I hope everyone else realizes it as well. My reason for using it is that it illustrates the fact that translation is a process of making choices, and that it’s easy to satisfy yourself, but not so easy to satisfy a broad audience.

I would also note that I certainly don’t think there is such a thing as “an authoritative translation.” My article was intended to point out the next best thing for Bible students who don’t know the Biblical languages. For you and me, the authoritative stop will be at the texts in the source language.