The Passion Translation: Content Review

The Passion Translation has received considerable negative publicity while being supported in an equally passionate way, especially in the charismatic movement. You can find my overview on MyBibleVersion.com, and I presented an overview of criticism and of my review methods in a previous post.

How I Rate Translations

Follow the links above to see my rating of The Passion Translation, which also provides an example of how I do such a rating. I do not designate Bible translations as “good,” “bad,” “ordinary,” or some other generic designation without regard to context. I prefer to rate a translation for strengths and weakness in different areas.

The chart provided shows numeric ratings. Many of these are themselves subjective. I use word counts to determine how formal or functional a translation is. By functional, I don’t mean that the translation works, but rather that it translates in order to provide equivalent impact on the target audience to the original. A formal translation attempts to match specific words or phrases to source words in the Greek, Hebrew, or Aramaic text.

But having done a word count in a specific passage (I start from Hebrews 1:1-4, which tends to force some rewording), I also look at other passages to see if that number works. Thus the numbers provided should be considered a personal opinion on each item.

Specific Notes on TPT Ratings

In the case of The Passion Translation, my own key takeaway was that the overall impact of a translation may be badly skewed by either its critics or its proponents. In the majority of cases, I found that passages were precisely what I would expect of a missionary translator. This doesn’t mean that the translator’s theology has no impact. Everyone’s translator’s theology has an impact. One cannot translate without interpreting, and one’s interpretation and theology will be tied together. What surprised me, after first having heard the hype, was how expected the renderings were.

Of course, ratings such as whether a translation is by a committee or an individual were fairly clear–this is an individual translation. In addition, it’s clear that the translator is in the charismatic movement, and specific related to the New Apostolic Reformation. Nonetheless, as I’ve stated before, when you have the translated work in front of you, the proper approach is to examine that work.

In terms of formal vs functional, I found that TPT was closer to formal and less free in rewording than I would have expected from the criticisms. It definitely reflects a willingness to reword and rework passages for the target language and audience. Yet I found it less likely to do so than The Message.

My initial word counts from Hebrews 1:1-4 actually indicated considerably less rewording than I expected, and after reading a number of other passages, I edged the ratings a point higher on the “functional” scale and a point lower on “formal.” One might describe this as a dynamic or functional translation with some significant deviations.

Specific Renderings

Ephesians 5:22

In my previous post regarding the hype about this translation I included a video. In that video, the translator claims to have received a new translation from God (discussion starts about minute 20:00). I won’t go into this in detail, but on linguistic grounds, I would have to reject his suggested translation.

Why? First, I would not accept his claim that Jesus and the apostles worked entirely in Aramaic, and certainly not that the book of Ephesians was written in Aramaic. There is no evidence to support the latter at all, and I find any evidence regarding the gospels to be quite weak. Second, the Peshitta, which is the closest thing we have to an Aramaic version, reads very much as the Greek does.

Note that I would not list this as an error. It’s a strong difference of opinion. I wouldn’t mind if the text read the way TPT reads. I’d be very comfortable with that. But I can’t support that linguistically.

Because of the intensity of criticism, however, I need to note here that I disagree with most Bible translations at some point. Practically anyone who reads the Bible in the original languages will disagree with any translation at some point or another. Disagreement is different than rejection.

(For those interested, my friends Elgin and Hanna Hushbeck have written a book in the Topical Line Drives series from Energion Publications, To Love and Cherish, which goes into this passage in depth, based on the Greek text.)

Psalm 110:1

Yahweh said to my Lord, the Messiah:

Psalm 110:1 (TPT)

“Sit with me as enthroned ruler

while I subdue your every enemy.

They will bow low before you

as I make them a footstool for your feet.”

There are a few interesting points here compared to the Hebrew, and they’re worth noting in understanding the nature of the functional approach to translation, along with some “transculturation.”

The use of “Yahweh” has not been traditional in English translations, but here it literally reflects the source text. The traditional approach has been to use LORD for “YHWH” and “Lord” for the Hebrew word “adonay” while using lord for the same word with reference to a human ruler. (Note: I use loose transliteration of the Hebrew to make it easier for readers who don’t know Hebrew. In this case, however, it’s worth noting that “adonay” is “my Lord” with a plural of majesty, while “adon” is just “lord” and “adoniy” is a singular “my lord.”)

Thus in traditional translations the first line of this verse comes to something like “The LORD said to my L/lord,” with the capitalization of the second “lord” depending on how the translators interpret the verse. Read Messianically, it would generally be capitalized. Read as a blessing on an earlier Israelite king, it would not. I can testify from teaching experience that the LORD/Lord/lord difference can cause some confusion.

Thus in the first line, TPT makes an interpretation quite clear. The translator is conveying a Messianic interpretation, and clarifying the difference in the terms for English readers. In case the capitalization is insufficient on “Lord,” he adds “the Messiah.”

One might complain that a reading that is non-Messianic would now not be possible, yet at the same time, the clarification of the fact that the two instances of “lord” (however capitalized) represent different words makes another aspect of the verse much clearer. Translators regularly make this kind of choice for readers. There’s no avoiding it. You can’t convey all the potential meanings.

So in the second line with have “Sit with me as an enthroned ruler.” This is a more equivocal kind of clarification, a case in which the translation is clearer than the source. Formally, the first part of the Hebrew reads “Sit at my right hand.” This would indicate a position of trust and authority. Some might regard “as enthroned ruler” as an overstatement. James and John as to be seated at Jesus’ right and left hand. This would have meant that they were the first and second rank below Jesus in His kingdom.

In either a messianic or a royal enthronement context, however, “enthroned” doesn’t miss the point.

The remainder of the verse is quite valuable in indicating the nature of this translation. Formally, I would translate the Hebrew text as:

Until I place your enemies as a footstool for your feet.

Psalm 110:1b, formally translated

And the TPT:

… while I subdue your every enemy.

Psalm 110:1b (TPT)

They will bow low before you

as I make them a footstool for your feet.

So what’s going on here with all the extra words?

The translator is trying to present you with imagery that will help you understand the meaning of making enemies a footstool. The imagery would likely have been well-understood by ancient Hebrew readers, but words like “subdue” and “bow low” help create a picture.

You can argue that this is “technically” not correct, though I would ask simply what it is that should be translated when there is poetry that contains rather vivid imagery. What does a translator convey, and how? Both The Message and The Passion Translation often choose to substitute imagery or expand on the original imagery in order to evoke a relevant picture for the readers.

If you find this disturbing, there are a multitude of much more formal translations with which you would be more comfortable.

Galatians

To get a broad feel for this translation I listed to Galatians via Audible. I did this while walking and all in one session. There were only two issues that I noticed.

The first is quite minor. I would definitely nuance Paul’s use of the term “law” in Galatians differently. This is definitely not an error, but rather a difference in presentation. I think it’s important to be clear that while the specific example of law that is the primary issue in the churches of Galatia is the Jewish law, Torah, Paul is making general points about the function of law. I found this eclipsed to some extent.

The second is one that I have noted about many paraphrases. Challenging, in-your-face statements are sometimes weakened. One such statement is Galatians 5:12:

12 I wish that the ones who are disturbing you would also castrate themselves[c]!

Galatians 5:12 (LEB)

Now try The Living Bible:

12 I only wish these teachers who want you to cut yourselves by being circumcised would cut themselves off from you and leave you alone![a]

Galatians 5:12 (TLB)

Slightly less in-your-face, isn’t it? Note here that The Message keeps the cutting-edge on this, so to speak!

Now try The Passion Translation:

I wish they would go even further and cut off their legalistic influence from your lives.

Galatians 5:12 (TPT)

It is important to note, however, that TPT has a footnote indicating the alternate translation. I’ve made comments on this elsewhere. A footnote is a good option when there are viable alternatives or when it’s impossible or just clumsy to get all the meaning packed into one translation.

Conclusions

I could go over many other passages, but not that much would be gained for purposes of a review.

My negatives regarding this Bible translation are that it is done by an individual, that it is very definitely fixed in the charismatic tradition stream, and that some of the hype tends to be distracting. While this doesn’t mean that the translation isn’t valuable, it does mean that it is not well-suited to discussions between traditions.

The hype, unfortunately, tends to center on God’s call to the translator to produce the translation. (I ignore here the standard complaints that amount to “the translator didn’t translate my favorite verses the way I prefer.”) I personally think that this translator, as well as many others, have been called by God. That call is not the guarantee of their translation work. Solid linguistic work makes a translation good.

Contrary to my expectations based on what I had heard and read, however, I do not have major problems with the translation itself. One should always take into account the biases of the translator(s). These biases are made clear. That’s all one should expect. There are no sneaky surprises.

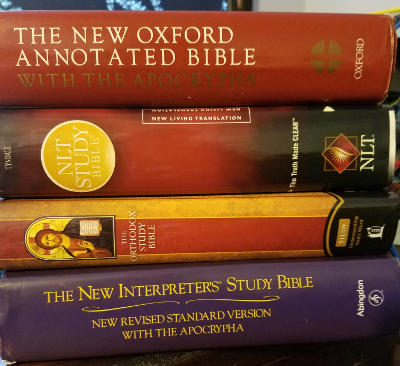

If you are studying, I would recommend comparing more than one English version. For example, using The Passion Translation alongside a Bible with interfaith participation in the committee, such as the Revised English Bible, and perhaps a more evangelical formal translation, such as the ESV, would help you be sure you’re hearing God’s Word in the text.

One Comment