Perfection and Maturity in Hebrews 6:1

Perfectionism is an interesting trait, and can be quite destructive. United Methodist pastors are still asked whether they are going on toward perfection, though I have found few who expressed great comfort with the required “yes” answer, and not a few who had their fingers crossed.

The line comes from Hebrews 6:1, and the more I study Hebrews, the less I see this in terms of attaining a moral standard. John Wesley himself made it clear that “Christian perfection” would be a gift of God, given by grace, and not an attainment (repeatedly stated in his compilation A Plain Account of Christian Perfection).

But what is the perfection to which a Christian should go on toward?

Before I look at that, let’s ask about the verb that is being rendered by “going on” here. This is almost universally translated actively, taking it as a middle voice. (Let me skip all the arguments about the middle voice here and just say that in this context, a middle does justify an active translation.) But it can also be taken as passive, and I think it should.

Let me quote David Allen:

…The verb may be construed in the middle voice in the sense of “to bring oneself forward,” but most likely it should be taken as passive, suggesting God as the one who moves the readers along to the desired goal. Christians are dependent upon God and his grace to enable them to press forward to maturity. (Hebrews, The New American Commentary, p. 400 [Nook Edition])

(I was helped to a decision on this in a discussion with Dr. David Alan Black, who should not be blamed for the rest of this post!)

This fits well with what I see as the message of Hebrews in general, which I summarize as “get on the right train and stay on it until it reaches its destination.” Human action is called for in the book of Hebrews, yet it is always action that is empowered by God, and not by us.

But the other side of this is what sort of perfection is involved. In learning we’re often told to go find the definition of a word in the dictionary and then we think we understand a passage we’re reading. For building language skill, that’s not a bad plan. But for coming to understand a relatively complex piece of theology, it leaves something to be desired.

Biblical languages students start by learning glosses for (a word or phrase seen as an equivalent), then learning that there are numerous possible glosses and that the lexicon provides such lists. After they have become skilled at this process, one hopes they will learn to work with definitions and semantic ranges for the words. But even at that stage, the tendency is to discover what a word means in scripture and then to force that meaning into the text.

I think that’s what is happening here. We see this verse as demanding that we continue the quest to attain a state of moral perfection. But in the book of Hebrews our task is to continue in Jesus, our High Priest. If we stay the course with Him, we will attain the promises. (I’m not going to reference everything here. Many of these are themes stated repeatedly and in different ways through the book.)

We might also consider the perfection of Jesus, who is “perfected” through suffering (Hebrews 2:10). Clearly, Jesus is not brought to a state of moral or ethical perfection. Rather, he is being perfected as a High Priest, acquainted with all our weaknesses (Hebrew 4:14-16) but also above us all in all ways (Hebrews 7:26-27), the perfect person to be the communicator or mediator between God and humanity. In this case we’re looking at a definition on the order of “totally suited to accomplish a particular mission.”

I might use this sense in recommending someone for a job. The “perfect” candidate is not one who is never going to make any mistakes, nor is he necessarily a person who is known never to engage in sexual misconduct off the job. Rather, that candidate is the person who is fully qualified to carry out the assigned tasks. It doesn’t mean he’s not wonderful in all those other ways; it’s just not the element in view.

Thus Jesus can be perfect and need perfecting all at the same time, and we see this developed from Hebrews 2-4. Hebrews 5:9, which immediately precedes our passage (I consider 5:11-14 as the first step in an argument that continues in 6:1. The chapter break separates this in a less than helpful manner.

So now we look at the state of the audience. They are stuck at basics and not ready to understand the discussion of Melchizedek which he wants to start. So having noted both the weakness and what strength would look like, he suggests that we lay aside the basics (the milk) and go on to the meat, whereupon he does precisely that.

“Let us be moved along toward perfection …” calls us away from basics and on to the meaning of this high priesthood. There is, I believe, a call to action and yes, to holiness, in moving on doctrinally, but the call here is to get past basic thinking and move on toward more mature thinking. Let your minds be perfected.

As I’ve commented before, students of Hebrews often divide the book into doctrinal presentations and exhortations. It’s not entirely wrong to differentiate, but I don’t believe these two elements are all that separated for him. The understanding of the Melchizedek priesthood of Christ is, in itself, a call to new action.

“Being carried on” or “being moved on” toward perfection is passive in form, but being carried by Christ is a rather active passivity, as we might deduce from Hebrews 11. Note how the preparation for solid food is through exercising one’s faculties.

Active passivity. Gracious working. It might just describe life “in Christ”!

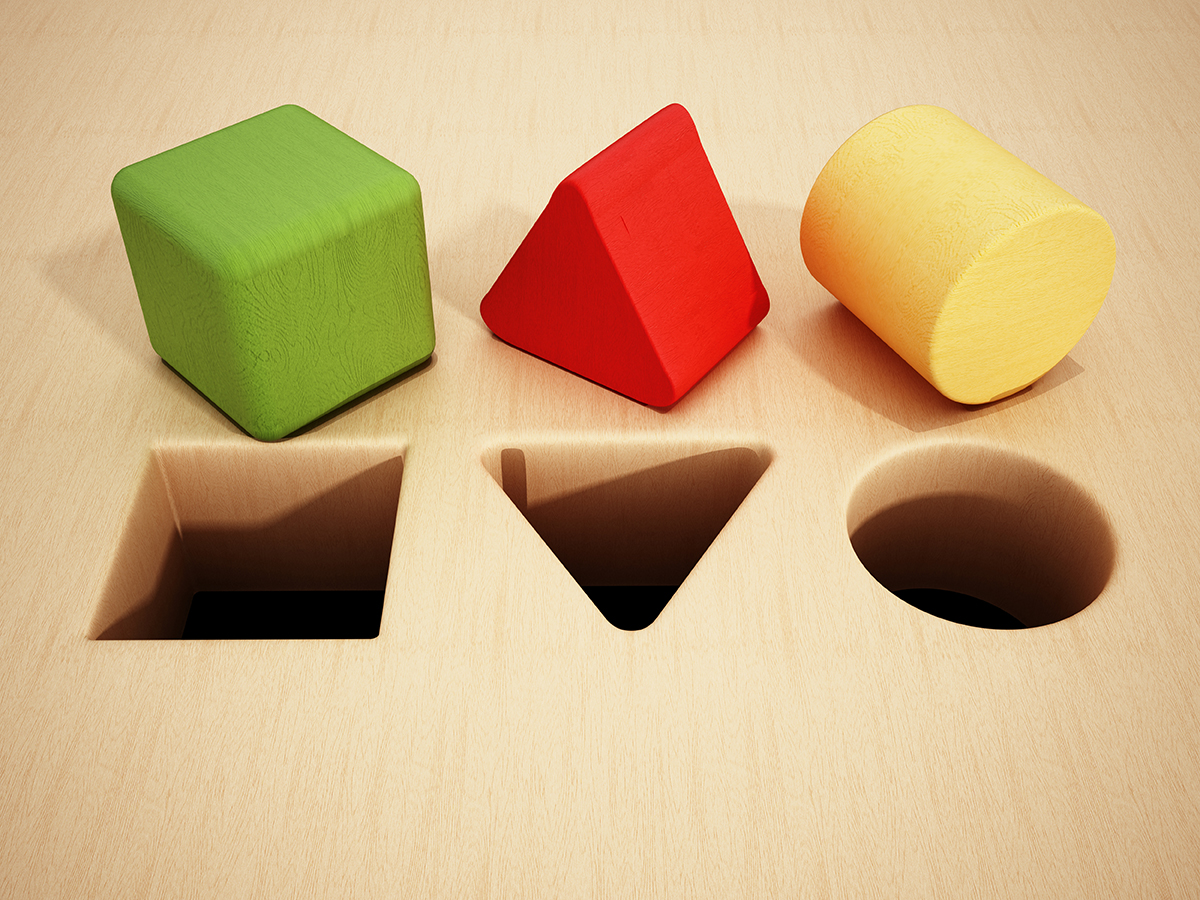

(This post’s featured image is licensed from Adobe Stock, #115932220. It is not in the public domain.)