Lectionary Texts for Transfiguration – Cycle A

I want to make just a few remarks on the texts selected for Transfiguration Sunday, February 3. I like to find common themes in the lectionary texts even when they don’t seem all that coherent. In this case, the texts are quite carefully chosen.

First is the story of the transfiguration from Matthew 17:1-9. There are a couple of things to note about the differences in the transfiguration stories in the various gospels. Working from Darrell Bock’s Jesus According to Scripture (p. 235), note that Luke is the only one who mentions that the disciples slept. Mark and Luke both tell us that Peter didn’t know what to say, while Matthew does not. Luke notes the fear when the cloud appears. Matthew has the disciples fall down in fear at the voice.

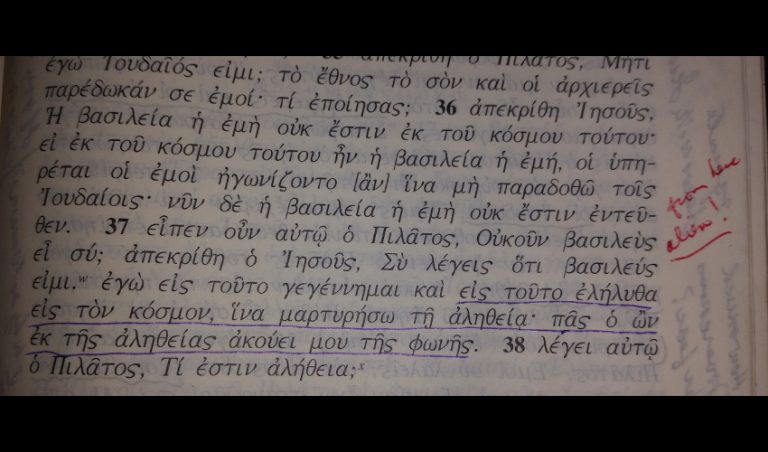

Our Old Testament and Epistles readings bracket this event. Moses goes up to Mt. Sinai and into the cloud in Exodus 24:12-18. Quoting Bock, p. 235: “A new era and reality appear with Jesus and the glory that his presence represents.” This is an important point, and one could build a sermon around this shift of emphasis. One of the things I notice repeatedly in discussions of scripture between Jews and Christians is that while we generally argue verse by verse, especially asking whether this or that is a Messianic prediction, we rarely discuss the overall difference in view.

For Jewish interpretation, the Torah (Pentateuch) is the heart of God’s revelation, and everything is interpreted in relation to that. In Christianity, the Torah appears practically to get dismissed, and Jesus is the central element of Christian interpretation. We interpret everything in the light of the cross, no matter how we view the cross itself. How we view it is important, but it remains central. In terms of scripture, that places the four gospels at the heart of Christianity as the Torah is at the heart of Judaism.

If you look at our lectionary readings, and compare them to synagogue readings, you’ll see the same thing. We center around a gospel passage; they around a Torah passage. This particular scripture is partial justification for that Christian approach. Jesus is presented as a second lawgiver, and the command is given to listen to him.

The epistle, 2 Peter 1:16-21, introduces a later testimony and also the explicit connection of transfiguration with a confirmation that Jesus fulfills (in the sense of “makes complete”) the scriptures of the Old Testament. That, of course, is a subject in itself. One sermon might be the topic of type-antitype-testimony, and the importance of the testimony to each event. Peter, James, and John saw Jesus on the mount of transfiguration. Only Joshua went into the cloud with Moses. The written testimony is important in carrying all this through.

Those with a more critical mindset (and congregations to go with it) might discuss the different views of a passage such as this. The obvious construction tying themes from Hebrew scriptures into the life of Jesus suggests that the story is written precisely to make that particular connection. There are two extremes. On the one hand one can imagine that the story was created precisely for the purpose of presenting Jesus as the new lawgiver, and didn’t actually happen at all. It’s edifying Christian fiction. On the other hand, one can assume that the reason this happened is that Jesus is, in fact, the new lawgiver, thus God did for him something similar to what he did for Moses.

Finally, Psalm 99 is simply a celebration of God’s presence, with a number of allusions, including the temple (“on/above the cherubim”, verse 1), the pillar of cloud (v. 7), and the holy mountain (v 9). It would make an excellent call to worship.