On Being Christian and Killing People

I was reminded this morning that it was Veteran’s Day, not that I had forgotten, because I got an early note of thanks from my wife, who regularly thanks me for me military service, defending, as she always notes, her freedom. At the same time, I will either read or hear from some Christian friends who will say that military service is not compatible with being a follower of Jesus. This year, this function was served by my friend Peter Kirk, who is not happy with acts of remembrance in church, of which he says:

If military people wish to have their own parades to mark their fallen comrades, they are welcome to do so. But please can they do so well away from the churches, whose fundamental attitudes are, or should be, completely at odds with theirs. And please can churches stop pandering to the expectations of those in the world outside, and of those among their own numbers, who hold anti-Christian militaristic views and expect the church to hold ceremonies for them, and disrupt its own regular programmes to do so.

Now my point here is not to go after Peter or his position on this issue. What interests me on this is simply that I have many people in my life who simply would not be able to hear one another’s position. Many local Christians that I know consider pacifism a crazy notion held by people who aren’t really quite Christian, and probably live in California. They would be very surprised to meet Peter, hear his authentic testimony of Christian faith, and yet find that their views on war are so diametrically opposed.

I have an interesting family history here as well. My father spent part of World War II planting trees in Canada because he refused to bear arms. He was willing to work in the medical corps, a reasonable option considering he intended to be a physician, but he was not accepted into that form of service, and because he refused to train with or carry a weapon, he was given alternative service. He lived to see both his sons serve voluntarily in the U. S. military.

My father’s religious background was Seventh-day Adventist, many of whom reject bearing arms, but will serve in the military in medical capacity. One thing I found disconcerting about growing up in SDA communities was the rather large number of people who would reject personally bearing arms and yet voted for the most pro-military and pro-war candidates that were available. I have a much greater respect for pure pacifism than I do for those who refuse to do the killing themselves, but vote for the policies that lead to others doing so.

A few years ago I was teaching a group of teenagers at a United Methodist church, and I found that the one thing they wanted to know about me was whether I had ever personally killed anyone while in the military. As a veteran of the U. S. Air Force, that is unlikely. The Air Force is not generally very “personal” about killing, and I was simply a cog in the machine that made it happen.

I don’t believe that relieves one of responsibility. I consciously chose to be in that position. I chose the particular job I wanted in the Air Force. I knew what I was doing, and I re-enlisted to continue to do what I was doing. I was not a practicing Christian at the time, so it is appropriate to ask whether I would still do it.

The answer is yes. I’ve written about my position before in a post titled Why I Am Not a Pacifist. I think that there are circumstances under which peaceful protest is the correct approach. I think there are circumstances in which one must suffer evil silently. But I also believe there are circumstances in which one needs to respond with force. The state doesn’t carry the sword in vain, and my citizenship in this country in this world means I may be called upon to carry out my part.

A peaceful protest or civil disobedience is an approach that depends on the conscience of the enemy. There are times when one faces an enemy without a conscience. Peaceful protest often works by wakening the consciences of others who will bring force to bear. There need to be people with an ethical approach to bringing such force.

I recall a conversation while I was in the Air Force. Since I was stationed at Offutt Air Force Base, headquarters of the Strategic Air Command, we got an unusual measure of the nuclear freeze protesters, which was the major movement of the time. A group of us were discussing this, and most indicated they were annoyed to be defending the freedom for people to protest against them. Flag burning even got into the discussion, though I don’t recall any flag burning amongst the freeze protesters at the base. They were generally painfully courteous about their protests.

And indeed those protesters couldn’t have been doing the same thing on the other side of the conflict of the time. They were using the freedom for which we might be called to pay in order to protest against us.

But for me that was precisely the reason for me to be there–to defend the freedom of people to annoy me in any number of ways. That freedom was what made it worthwhile to serve in the military and to be prepared to be there in time of war.

It’s worthwhile noting that as a voter, I would have opposed every one of the wars in which I was involved (Grenada, Panama, and the first gulf war). I don’t think they were well conceived. At the same time, I believe that having a democracy in existence with the military force to stand against communism was absolutely necessary, and that helping to keep that democracy safe was a good thing.

Those who are regular readers of this blog will know that I have opposed the current Iraq war since before it started. But I want to be clear that my opposition is not to the use of force. Sometimes actual use of force is required. Frequently, the ability to effectively use force is necessary.

There are those who will respond only to force. For those force is ready. For this reason I look back on my own 10 years of service with satisfaction, and I thank all those others, especially those in those jobs that require one to get more personal about killing, not to mention being killed.

It’s because of you that I can engage in this debate.

Henry, thanks for interacting with me. As it is my bedtime I can’t respond to you adequately now. Just let me clarify that I don’t necessarily take a strictly pacifist position, but I do think that military and indeed political matters should be kept separate from the church. There is a case to answer about defending our freedoms, when they are under real attack – but from Grenada and Panama? or even Iraq?

Peter – I oppose actions such as Grenada and Panama which were not justified, and actually think that the action in pushing Iraq out of Kuwait in 1991 was questionable. These are all actions for which I have the “been there” ribbon.

I need to say more, but I believe there’s a different line between support and opposition politically for a war (how I would vote) and whether one, as a member of the military, must just say no. At least the international community definitely has certain actions to which a soldier is expected to say “no.”

I’ll post on this some more.

I agree with your comments and respect those who hold pacifist positions, although I find it hard to understand. It is sometimes difficult to have conversations with strict pacifists, however they probably feel it’s difficult to converse with me.

Niebuhr was called the Christian Realist because his views evolved from pacifism to an understanding of how a Christian can support war. I think more along his lines.

And a big thank you for your military service.

Niebuhr is an interesting case. These debates often end up with examples from Nazi Germany, which provides some of the nearest examples of black and white issues that we have.

I would call myself a ‘soft pacifist’ and, basically, I would say that war and violence are always sinful but that sometimes in the course of human society, it may be necessary to choose violence as the best of a set of bad choices.

I feel that a person could make this choice on the basis that ‘This is a sin but God sees that I have no other choice and I’ll have to trust in his forgiveness.’ In my view this is a vastly different position from ‘supporting’ war. To support war, in my view, is to say ‘God blesses my choice to kill others’.

As a pacifist, I feel that I’m constantly told that I’m ungrateful for the sacrifice that people made in ‘The War’ (this usually means WWII). *I* fail to understand why a person can’t say ‘War is wrong’ and simultaneously recognise the sacrifices that people have made.

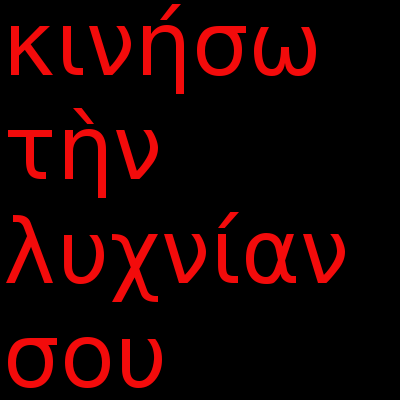

If there will be no war and no killing in the Kingdom of God, then how can God bless war? Why do we call Jesus The Prince of Peace at Advent and Christmas?

Pam-I don’t mean to tell you you’re ungrateful. Growing up in the household that I did, I truly came to understand that one can disagree. My brother has always been equivocal on these issues. My father and I, however, remained on opposite sides for his entire lifetime.

I think that’s often missed in these discussions. My father, like many other conscientious objectors, put himself on the line for his convictions, as I did for mine. We need people to do that.

This needs more than a paragraph answer, but I think that I disagree with you substantially. For me, ethics occurs in the real world, and the issue is making the best choice under the circumstances. If violence is ever the best choice, then the person who makes that choice when it is the best choice does the right thing, and I believe God would bless.

I don’t believe any of our actions are really pure, and it’s hard to be sure when violence is justified, but that’s what our wills are all about. God knows who and what we are, and responds accordingly, in my view.

Pam’s comment resonates strongly with me. Personally I am no out and out pacifist. I have known a number who are. Neither am I a “shoot first ask questions later” type, which I cannot reconcile with the Gospel. To give an Englishman’s perspective on Pam’s views, I have been much influenced by a chapter in Johyn Stott’s book, “Issues Facing christians Today”. To me war is one of those issues where as a very last resort it may be the least of evils.

So I have tended to view each conflict individually over the years. I was OK with ejecting Iraq from Kuwait in 2001. I have been very unhappy about the current conflict. I shed few tears for Saddam, but removing a regime we detest by force does not seem to me adequate basis for war. Iran could take a similar view about the USA or the UK!

While I detest war and see at as a matter for repentance, I conclude it is still right and proper to honour and remember those who have given their lives, whether through volunteering or conscription., and on occaisions to do that within a church setting. In that respect, those who already follow Peter Kirk’s blog, will realise that is an issue on which we amicably differ.

Colin-you sound closer to the way I feel, though I have some serious questions about 1991 (don’t feel bad about the date slip!), as well as the present war.

There are few wars that I think are truly necessary.

I think many wars are matters of repentance, if the war itself is inherently unjust or the prosecution of it is unjust. How many wars are, ultimately, about material gain or pride? Most wars are wrong. I consider it the duty of every person of conscience to stand up against unjust wars.

But it seems to me that the pacificism movement contains an effort to turn itself into the new Purity Code, with some insisting that always and at all times “violence” is inherently wrong. I wonder very much what they will make of the Last Judgment and whether God’s ultimate use of force/superior power to stop evil will be objectionable. That’s serious, btw; I’ve noticed many universalists amongst the pacifists, in that they have so far committed themselves that “violence” is categorically and inherently sinful that they must conclude that God is incapable of it.

If a pacifist took pacifism to the extreme of standing by and watching a people be annihilated rather than get their hands dirty to help the oppressed — in that case, pacifism is the sin. In the case of the destructive rampage by “an enemy without a conscience” as Henry so aptly put it, the soldier is the man of God and need not repent. The pacifist, in that case, should be the one repenting. It is morally wrong to put personal purity — or the blood of the murderers — above the blood of the innocent.

—

Ok, back off the soapbox now.

Take care & God bless

Anne / WF

Anne-quite a nice soapbox. Don’t be afraid to climb up on it! I hadn’t thought of the similarity to the purity code. That seems similar to my view that we have to make decisions in the real world on ethical matters, and God know that we do.

Whoops, I meant 1991 for the Iraq/Kuwait episode. Sorry I had a fraught day and was about to start our house Group

Pam, Colin and Anne, I don’t think my position is far from any of yours. In 1991 I supported the ejection of Iraq from Kuwait, but I’m not sure I would now as my position has developed. I suppose I am happy to recognise what Pam calls “the sacrifices that people have made” while preferring to avoid that pseudo-religious terminology. But I differ from Colin in wanting to keep this kind of recognition outside church, at the very least unless accompanied by a strong “war is wrong” message.

I’ve been wrestling with the same question (although from a humanist perspective obviously). Thanks for the input, life makes a bit more sense now.

It really all boils down to tolerance.

http://powerofpride.wordpress.com/