Openly Discussing Evolution, SDAs, and the UMC

Evolution is one of those issues we often don’t discuss in church. There are actually quite a number of Christians who accept evolutionary theory in general or just a part of it, but quite often they just don’t want to get into the kind of acrimonious debate. Every so often (really quite rarely, all things considered) I’ll get an e-mail from someone who found my e-mail address on the list of board members for Florida Citizens for Science, and they wonder how I can be a Christian and be on that list. That is, unless they simply assert that I must not actually be a Christian. (This is a rambling post. [Which of mine aren’t?] Toward the end I do get around to referring to the SDA church in which I grew up and the UMC, where I currently hold membership.)

Now this post is more about “openly discussing” than about evolution as such. I grew up in a conservative Christian culture (the Seventh-day Adventist Church), in which it was one of the articles of our faith that we accepted the literal creation week. As a result of that, and of the resistance I met when I started to see things differently, I grew up with the impression that conservatives want to close off conversation while liberals were open. Each group was, after all, treating me in that way.

But the more I have experienced the world, the more I have observed two things:

- Any entrenched group will tend (or at least have a strong temptation) to exclude outlying opinions

- Outlying groups, especially those that actually have some traction, will tend to feel excluded even if they aren’t

The fact is that no matter how energetically we may work to be totally open, no discussion can take place on a completely unlimited field. Not all boundaries are limiting boxes.

A few years back I was teaching a Sunday School class and one of the members asked me to meet with him to discuss the future of the class. He wanted us to study eastern religions. I told him that I had no problem with the class studying eastern religions if that was what they wanted to do, but they’d have to get a different teacher. “Why?” he asked. Well, I explained, there are two reasons. First, I know very little about eastern religions. Second, I’m a Bible teacher. That’s what I do. He was quite surprised and told me that I didn’t really need to know much about eastern religions in order to teach it for the class.

That attitude is more common that you might think. On the one hand we have the idea that issues can only be discussed by a very highly qualified group of experts, and outlying opinions, those contrary to the majority position, should shut up and go away. That attitude can lead to stagnation. But on the other hand we have the view that all opinions need to have an equal place at the table, no matter how poorly supported they might be. This is another attitude that will prevent progress, this time by creating chaos and wasting time.

We live in a kind of tension between these two ideas. For example, I believe that creation vs evolution is a perfectly valid subject for discussion in the church. The debate on the interpretation of Genesis is alive and well, and carried out by highly qualified scholars in the appropriate fields. I think that there is really very little actual scientific debate on this same controversy, because I don’t see creationists doing original science that can actually challenge the various facets of evolutionary theory. I see some picking at this or that, but nothing one can get one’s teeth into. But I’m not a scientist, and I’m not qualified in any of the fields in question, so my opinion on that point isn’t particularly important.

What I think we should work toward is a creative tension between consensus and new ideas, between open discussion of all views and perhaps more productive discussion between people who are more selective. I think this sort of discussion is well served by a variety of confessional, non-confessional, and secular schools, whether the topic is religious or not. I regularly hear complaints that certain sectarian institutions should be shut down because they are too closed in their confession. I disagree. As long as those who attend know what the principles of the school are, and graduates are functional in the subjects they learn, I think that’s an appropriate way to add variety.

The problem is that “functional” is defined by too many people as “accepting what I already believe.” As an example, I hear from advocates of the historical-critical method in Bible study (and with some caveats I count myself among their number), that one isn’t “qualified” in biblical studies if one doesn’t “know” something so obvious as that there are three Isaiahs. But what if one knows that this claim is made, and knows why, but doesn’t accept it? One can be so absolutely certain of one’s scholarly conclusions that one cannot imagine an intelligent person disagreeing.

Conservatives will doubtless nod and agree, but from them I hear that if someone can’t make a good argument for the 6th century dating of Daniel, or for the Mosaic authorship of all or part of the Pentateuch, that person doesn’t really know what she or he is talking about. Or perhaps the secularly educated scholar doesn’t truly understand Calvinist theology. Or Arminianism. Whatever.

My suggestion would be that if all your knowledge comes from one source or type of source, such as all your academic ideas are those favored by the school from which you got your degree, you may be a bit narrow. And that means that the simple fact that your college is confessional on the one hand, or very secular on the other, doesn’t mean you’re ignorant or closed. Ignorance and closed-mindedness are cultivated attitudes. Especially in modern America, you have no excuse not to know how the other side thinks.

You also have a variety of avenues to challenge the other side, so you don’t really have an excuse when one school or organization doesn’t like your ideas and tells you to hit the road. I may not like it. I too have an ideal academic environment, one in which serious scholars who disagree are welcomed irrespective of confessional statements. But that’s my imaginary ideal. I think I got a rather decent education from confessional schools that were closed in many ways I wish they were not. But they were nonetheless good schools.

All this blather has been leading to two links with quick opinions on my part. The first comes from a Seventh-day Adventist source, in which an SDA writer responds to some claims of supposed challenges to evolutionary theory. It’s in Spectrum Magazine, titled Dangling or Not? A Response to Chadwick and Brand. This article critiques another in which creationists see some new scientific discovery challenging the foundations of evolutionary theory. Just as I’ve been hearing all my life that the end of the world is upon us because of some recent story in the news, so I have been hearing that evolutionary science was on life support due to some new discovery. I’ve become just as jaded to both. But this story takes place in an organization that really doesn’t want to open the door to full discussion of this issue. Being an advocate of evolutionary theory in the SDA educational system is unlikely to be good for your career prospects.

On the other hand we have the UMC general conference. Now in religious terms, as I’ve said, I see creation vs evolution (though I don’t see the two in conflict), as a valid debate. Amongst the advocates against evolutionary theory is the Discovery Institute. Before you read the rest of this, you should know that I truly dislike the Discovery Institute. I think they largely make what should be scientific and theological questions into political ones. But just because I don’t like them doesn’t mean they shouldn’t be heard in the church. Yet according to this article from UM-Insight, they were denied a booth at the UMC General Conference. Why? Because they are not in accord with our social principles. Hypocrisy anyone?

I recall when I first joined a United Methodist congregation, I asked the pastor if I had to affirm the social principles. He said, “Those? We don’t pay much attention to them.” I know a number of Methodists who would object to his saying that, but what he says is very accurate. The social principles are a box that few would like to be confined in, yet that provide an excuse for many things. Advocating to change them is a recreational sport. If the GC venue was running out of space, you have to exclude someone, but this is a particularly thin excuse. There are plenty of United Methodists, though presumably a minority, who would be sympathetic to the institute’s work. Many of them live in this area. I disagree, but in the church they should have a voice.

My problem with discussion is in the definition of terms. I could say, I don’t believe in such and such that you believe in, but how do I know exactly what you believe. We have used terms ad infinitum, till they have lost meaning. For example, If every act of God is a miracle, then the word has lost any distinguishing meaning for defining whatever act of God a miracle is. So, what is meant by “evolution?” I won’t start into the labyrinth of definition here, I am just pointing out the problem. Suffice it to say, one could fill probably pages with questions defining exactly what “evolution” means, and the answers to those questions would still lack enough meaning to distinguish exactly what “evolution” and “evolutionist” really mean. It is the same with the “Young Earth” theory, and the “Intelligent Design’ theory. How can we talk intelligently when we do not know what we are talking about? Please note, I said above that this is “my” problem. So this may not be a problem others have. But I am lost in the many terms for which I do not know the definition, how the one I am talking to really defines what he believes.

Actually your problem is not just yours, but is endemic to human discussion. There are a number of reasons, but one is that we like to claim favored titles for our own positions. Thus “evangelical” is not the same thing now as it was 30 or 40 years ago, nor is liberal, nor for that matter conservative.

In any discussion, one of the first points we need to cover is the terminology. This might seem to make the discussion take longer, but since it will also advance more quickly once terminology is determined, it’s still more efficient.

One of the great difficulties in discussing evolution is precisely the point you bring up. What is “evolution?” In this post I’m talking about evolutionary biology, i.e., the biological theory of evolution. I didn’t take a great deal of time with the terminology, because both articles I linked to relate to precisely that.

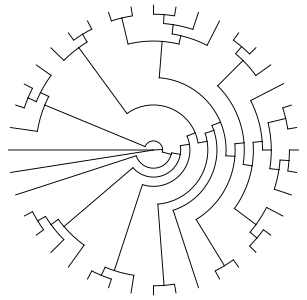

P.S. Would you please explain the meaning of the diagram which you placed at the beginning of your article.

It’s a radial phylogenetic tree. Each of the points would show a division point in the evolution of a population.

Thanks! I looked it up. Another word for it is “evolutionary tree”